When my husband and I moved to a suburb of Vancouver eleven years ago, many of our friends ribbed us wildly about our decision. Instead of living in a leafy urban neighborhood, a short walk from a good cappuccino, an organic fruit and veg store, and a pilates studio, we had, it seemed, forsaken civilization and migrated to the far barrens of Carland. Our friends could barely place our neighborhood on their mental maps, although it was a mere 20 minutes on the Skytrain–Vancouver’s rapid transit system–from where they lived. Others got hopelessly lost when they tried to drive here, even though the route was relatively straightforward, simple and entirely lacking in freeways. It was as if we had fallen off the edge of the known world.

When my husband and I moved to a suburb of Vancouver eleven years ago, many of our friends ribbed us wildly about our decision. Instead of living in a leafy urban neighborhood, a short walk from a good cappuccino, an organic fruit and veg store, and a pilates studio, we had, it seemed, forsaken civilization and migrated to the far barrens of Carland. Our friends could barely place our neighborhood on their mental maps, although it was a mere 20 minutes on the Skytrain–Vancouver’s rapid transit system–from where they lived. Others got hopelessly lost when they tried to drive here, even though the route was relatively straightforward, simple and entirely lacking in freeways. It was as if we had fallen off the edge of the known world.

But in spite of all the jokes, I’ve grown to love this peaceful suburban life. It’s quiet here. The air is clean. And I love the way kids play ball hockey in some of our streets. So I was a little puzzled this week to read that some researchers now view the suburbs as “sick zones” that promote diabetes and as “obesogenic environments” that actively encourage many North Americans to forego exercise and pack on the pounds.

To be sure, I see some of their reasoning. In neighborhoods like Vancouver’s West End or New York’s Manhattan, people have little need to drive anywhere. They can easily stroll to their neighborhood gym, bank or library. And ambling about such neighborhoods is pretty much a joy. Shops of all sorts, art galleries, restaurants, and little bars line the main streets: off them, stately old trees shade the sidewalks. Urban gardens bloom exotically.

To be sure, I see some of their reasoning. In neighborhoods like Vancouver’s West End or New York’s Manhattan, people have little need to drive anywhere. They can easily stroll to their neighborhood gym, bank or library. And ambling about such neighborhoods is pretty much a joy. Shops of all sorts, art galleries, restaurants, and little bars line the main streets: off them, stately old trees shade the sidewalks. Urban gardens bloom exotically.

Such environments clearly encourage daily exercise–no argument there. And clinical trials demonstrate that exercise, particularly in concert with a healthy diet, can reduce body weight and improve cardiovascular health. Moreover, just 30 minutes per day of brisk walking, five days a week, reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes, the adult-onset variety. So urban neighborhoods that lure people outdoors to run errands or stroll about for half an hour each day are doing their residents a big favor. Indeed one study published in 2004 showed that people who lived in highly walkable neighborhoods in Atlanta, Georgia, were 35% less likely to be obese than those who lived in less strollable parts of the city, such as suburbs.

But are all suburbs necessarily bad? Developers built the neighborhood I live in during the early 1950s, when the automobile was truly king. The houses are small and the nearest grocery store, bank and shops are a 30-minute one-way walk from home. As a result, my neighbors and I tend to drive whenever we have errands to do–something I wish weren’t the case for a host of reasons. But that doesn’t mean that we are all starved for exercise or that we rarely get out to walk.

Many people in our neighborhood, for example, have large dogs that need long daily walks. Our dog Max, a labrador retriever, averages about an hour and a half of leash-time a day. And he’s certainly not alone. The bigger, more energetic breeds–the retrievers, border collies, German shepherds–crave exercise. Without it, they soon become bored and destructive.

Many people in our neighborhood, for example, have large dogs that need long daily walks. Our dog Max, a labrador retriever, averages about an hour and a half of leash-time a day. And he’s certainly not alone. The bigger, more energetic breeds–the retrievers, border collies, German shepherds–crave exercise. Without it, they soon become bored and destructive.

Our neighborhood notably lacks in cool little streets lined with shops, bars and art galleries. Instead, it adjoins a heavily forested, 80-acre park threaded with walking and cycling trails. So we don’t lack for visual enticements: we have big Douglas firs and a ravine flush with person-tall ferns, and through it runs a shady creek where herons fish and owls sometimes hunt. Walking through it is pure pleasure. People flock there after work to unwind–young couples arm in arm, grandparents pushing prams, runners training for marathons. And on sunny summer mornings, elderly Chinese immigrants practice their t’ai chi moves at the edge of the woods.

I think that many suburbs richly deserve their rep for poor planning and energy inefficiency, with streets lined with McMansions and gas-guzzling automobiles. But I don’t think all suburban neighborhoods are created from one cloth and I certainly don’t see the suburb I live in as a sick zone or an obesogenic environment. It seems to me that researchers who paint the picture with such broad strokes are missing a lot of nuance. Indeed, I secretly wonder if they have ever spent much time in the suburbs.

Or are they like some of my urban friends, who think the civilized world ends at the city limits?

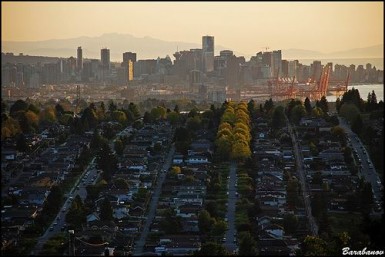

Photos: Top, View from Capitol Hill in Burnaby to downtown Vancouver, courtesy Miss Barabanov; Middle, Shop in Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighborhood, courtesy the last minute, Duncan Rawlinson; Bottom, courtesy Heather Pringle.

While in Vancouver yesterday, away from my suburban enclave of North Delta, I found myself longing for the urban life you describe but after recent media reports of our fair city costing more in housing than NYC or London I know it’s just a pipe dream. Can I ask which suburb you live in? If it’s Burnaby then those of us who live over a bridge still consider you city!

Andrea: Yes, you guessed it! But researchers would call Burnaby an inner suburb, while you reside in an outer suburb. And the housing prices in Burnaby reflect the fact that it’s suburban, not urban.

Heather.. if your friends think you’ve fallen off the edge of the known world when you moved to Vancouver, when I moved to Mexico, all my friends and family decided I

must be crazy & would be back in the US by 6 months.. but 13 years later I’m still here and loving it.

Sallie: Good story! And nice to hear these dispatches from places that are off the radar for most people.

Ask anyone at any gym or read the fine print on any piece of exercise equipment: weight loss cannot be achieved by exercise alone.

Your cited study says exercise may result in a whopping 1.1kg of weight loss.

I would suggest that our bodies maintain a balance and compensate for the exercise we do by consuming a few more calories.