I am a bit of a Civil War nerd. I inherited this interest from my dad. Together we have visited many of the Civil War’s top landmarks (we’ve even paid our respects to Stonewall Jackson’s left arm). But for all of the time I’ve spent on battlefields, I never gave any thought to the landscapes on which the war was waged until I read Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic.

I am a bit of a Civil War nerd. I inherited this interest from my dad. Together we have visited many of the Civil War’s top landmarks (we’ve even paid our respects to Stonewall Jackson’s left arm). But for all of the time I’ve spent on battlefields, I never gave any thought to the landscapes on which the war was waged until I read Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic.

In the book, Horwitz travels to the former Confederate states to understand how the Civil War still influences Southern culture today. At Shiloh, in Tennessee, he meets the park’s historian, Stacy Allen. Horwitz learns how Allen, a physical anthropologist, had debunked several myths about the Battle of Shiloh – and the war – with some scientific detective work.

As an earth science writer, I wondered: What do geologists have to say about the Civil War? A lot, it turns out.

I’ll give just a few examples. Pennsylvania geologists have written a geology field guide to Gettysburg, where igneous rock got the better of Robert E. Lee. Researchers at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have shown how loess – silt deposits that are accumulated by wind and often erode into steep cliffs – caused trouble for the Confederates at Vicksburg. And a physical geographer at Villanova University has demonstrated how the eastward flow of rivers in the Mid-Atlantic made it difficult for either army to hold its ground and win decisive victories.

I’ll give just a few examples. Pennsylvania geologists have written a geology field guide to Gettysburg, where igneous rock got the better of Robert E. Lee. Researchers at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have shown how loess – silt deposits that are accumulated by wind and often erode into steep cliffs – caused trouble for the Confederates at Vicksburg. And a physical geographer at Villanova University has demonstrated how the eastward flow of rivers in the Mid-Atlantic made it difficult for either army to hold its ground and win decisive victories.

But the most fascinating bit of Civil War geology that I found showed how sedimentary rocks could be a foe to both the Union and Confederate armies. When geologists Judy Ehlen and Robert Whisonant of Radford University plotted the war’s top 25 bloodiest battles on a geologic map, a pattern emerged: A quarter of the battles occurred on carbonate bedrock, and these skirmishes had above average causalities even among the worst battles.

It’s not a meaningless correlation, Whisonant told me in 2008. Carbonate, such as limestone, is a soft rock that easily erodes. Over millions of years, the forces of nature can whittle carbonate landscapes into relatively flat, open terrain, leaving few hills or ridges for soldiers to take shelter from gunfire.

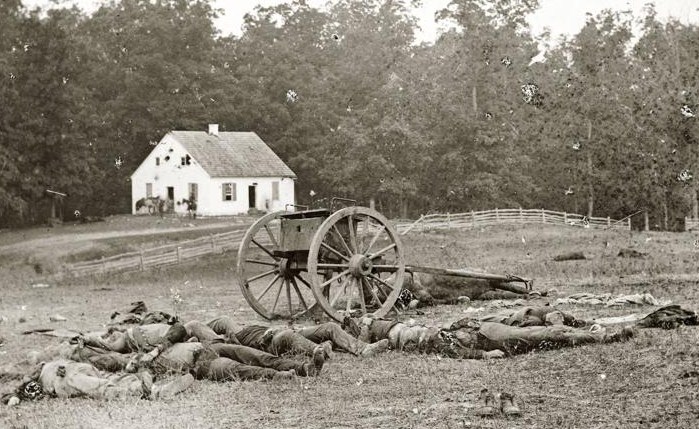

The dangers of a carbonate landscape are particularly striking in the case of Antietam (or Sharpsburg, as the Confederates called the battle). In just one day of fighting in September 1862, 23,000 men were killed or wounded, making it the bloodiest day of the war. The fighting took place on two geological formations laid down some 500 million years ago during the Cambrian period: the Conococheague Formation, made of pure limestone, and the Elbrook Formation, a mix of limestone, dolomite (another carbonate rock), and shale.

The dangers of a carbonate landscape are particularly striking in the case of Antietam (or Sharpsburg, as the Confederates called the battle). In just one day of fighting in September 1862, 23,000 men were killed or wounded, making it the bloodiest day of the war. The fighting took place on two geological formations laid down some 500 million years ago during the Cambrian period: the Conococheague Formation, made of pure limestone, and the Elbrook Formation, a mix of limestone, dolomite (another carbonate rock), and shale.

The differences in geology across the battlefield led to differences in topography. The land above Conococheague is largely flat and open, following the general pattern of carbonate terrains. The land above Elbrook, however, is more uneven because the formation’s different rocks eroded and weathered to differing degrees, creating a more rugged landscape with hiding spots for soldiers.

The differences in geology and topography at Antietam had a real impact on troops. In tallying up the battle’s death toll, Ehlen and Whisonant discovered casualties were at least three times higher in a flat part of Antietam called the Cornfield that sits atop the Conococheague Formation than in a more rolling area near Burnside Bridge that sits above the Elbrook Formation.

The differences in geology and topography at Antietam had a real impact on troops. In tallying up the battle’s death toll, Ehlen and Whisonant discovered casualties were at least three times higher in a flat part of Antietam called the Cornfield that sits atop the Conococheague Formation than in a more rolling area near Burnside Bridge that sits above the Elbrook Formation.

“Open ground being more dangerous for soldiers may not be news,” Whisonant told me, “but few people had tried connecting geology, terrain, and casualties on Civil War battlefields.”

Whisonant and other Civil War geologists who I have talked to all seem to agree that their work is not rewriting history, and they say geology is just one tiny factor that influenced the war’s events. That may be true, but these geologists are providing history buffs like my dad and me with something very valuable 150 years after the war began: a new take on the War Between the States.

__________

Erin Wayman writes about earth science and ancient life at EARTH Magazine, where she first reported on Civil War geology in 2008.

Credits: Dunker church – National Park Service; 2 paintings by Capt. James Hope, who was there; painting of battle at Burnside Bridge – B. McClellan

I live in a town that was both union and confederate. Battle of Fort Sanders — the university was shelled during the campaign to recapture Knoxville. At the time it was a major rail and river hub which fed supplies from Virginia to the south. At various point embargoes were staged on the river by dragging chains and catching barges headed south. Knoxville was definitely not a hot zone or the places you think of that decided the war — but ever so often a live shell is found in some creek bed that failed to go off.

As a West Pointer and former Green Beret, it makes sense the terrain rules. Every operation is planned with terrain in mind. I’ve walked all those same battlefields and will be at Shiloh next week. A great example of terrain totally dictating the battle is Little Big Horn. I never could figure out what happened to Custer until I visited the battlefield. As soon as I saw it, I could visualize what happened. I just released a book: Duty, Honor, Country a Novel of West Point & The Civil War and in the opening I explain why terrain dictated West Point’s strategic significance.

Bob, several of the scientists who I talked to about Civil War geology were at one point in their careers connected to the military. In fact, one of them taught military geography at West Point. As someone more interested in the social and political history of the Civil War, I had never given much thought to the importance of terrain until I started researching the geology.