“What can we do about high school physics textbooks?”

The question, I admit, stumped me. Not in the way that a question about whether gravity exists in other universes would stump me. That question I wouldn’t be able to answer because there isn’t an answer; the existence of other universes is speculative. This question, however, I couldn’t answer simply because I didn’t know that there was anything to be done about physics textbooks. I admitted my ignorance, said I would have to educate myself, and called on another raised hand.

Still, I couldn’t stop thinking about the question. It came during a Q&A session after a talk I gave last month at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. I had just spent 45 minutes explaining to an auditorium full of about 150 physicists the methodologies I use in trying to make science accessible to non-specialist readers, and I had been reading passages from my new book to illustrate my points. That whole discussion, I now realized, was predicated on the assumption that readers come to astronomy or cosmology knowing basically nothing about the physics of the universe, much like I do before I start my research. This ignorance isn’t exactly a given; questions about Newtonian dynamics or antimatter occasionally arose during my book tour. But if my overall experience was any indication, ignorance is a safe bet.

Afterward, in the hallway outside the auditorium, I talked to the person who had asked the question. A small crowd quickly gathered, and the conversation grew quite animated. The physicists, talking over one another, pressed forward. They wanted me to know, urgently wanted me to understand, that their field is in danger. Physics textbooks, they told me, are a generation out of date. Students aren’t coming out of high school wanting to be physicists. And why don’t they want to be physicists? Because they don’t know—can’t know—what physics is!

As I said, I don’t know much about textbooks. I know that the state board of education in Texas wields disproportionate influence over the content of textbooks across the nation because the state buys in such bulk that publishers use Texas standards as the lowest common denominator. I know that the Big Bang, along with evolution and global warming, occasionally emerges as a target for other antediluvian school boards. I don’t know what connection, if any, might exist between textbooks being out of date, as the Berkeley Lab physicists were claiming, and textbooks being incomplete, as I knew from news accounts. But I guess a widespread failure in the nation’s high school physics curricula—as well as a lost generation of potential physicists—shouldn’t have been news to me.

The validity of that news was reinforced a few days later when I took part in a conference call concerning a script for an IMAX-style movie about the current state of cosmology. Also participating in the call was a physicist at the University of California, San Diego. When someone on the call asked what a freshman (like our protagonist) coming to college would know about the dark energy revolution in cosmology (now 13 years old) or even the fundamentals of quantum theory (now more than 85 years old), the physicist just laughed.

A few days later, the severity of the situation wasn’t just further reinforced for me but complicated as well. After another Q&A session, a man identifying himself as a 30-year veteran of teaching high school science approached me. Not only are physics textbooks ridiculously out of date, he said, but high school science in general is being taught all wrong.

Oh, no, I thought. The problem isn’t just the textbooks? And it isn’t just Texas? It’s the teachers, too?

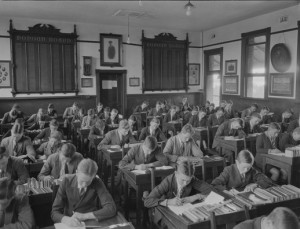

Teachers, he was saying, are presenting science as facts, facts, facts. Where is the excitement? he asked. How can students understand that science is a human activity? How can they discover the passion for themselves?

At last: a question I could answer.

“They need to hear,” I said, “that science is a narrative.”

(Next Friday, in “Talking Universe Blues, Part 3”: science as narrative.)

* * *

Image credits: Ryan Franklin (top); State Library of Western Australia

You should hear my-husband-the-physicist on the subject. “The pedagogy of physics,” he thunders, waving his arms, “is ALL WRONG.”

the question is not just about Physics.. but about high school.. it doesn’t matter what the subject is, high schools seem to get it wrong

Richard, as you imply it is the method of science that we need to teach. When science is trying to figure something out, it is then that it can be fun. Teaching “facts” is as boring as if learning how many plays Shakespeare wrote tells you about Shakespeare’s work. We should teach science that can capture students’ interest. Why not teach biology in an ecology class where the students do field work to map out an ecosystem? Why not teach physics using astrophysics [note I am an astronomer]?. Why not learn chemistry in the context of geology? Why do we teach biology, chemistry, and physics in that order? It is because we have been doing it for more than 100 years because it was in the 1890s that it was decided to do so. We need to revisit why we teach science and what it is we want students to learn.

While text books and science education in general do need to be updated I think it’s a bit ridiculous to expect high school students to understand advanced physics. Our high school students are under so much pressure to perform academically and athletically that they don’t have any time for fun. Even the nerds who like science need free time for their nerdy hobbies. Kids used to have time to tinker, now they don’t have time because they have to memorize a bunch of useless stuff so they can pass standardized tests. Real learning comes from tinkering and creating things. Older generations has Commodore 64s and Ataris to tinker with. The current generation has iPods, iPhones and iPad which are locked down, so they can’t tinker. We’re raising a generation of consumers instead of a generation of engineers.

Dear Richard,

As a student of Physics myself, we have some very good predictions and answers of our own. As you had been exposed to, the problem is one of pedagogy in general. For example, the majority of subjects being taught in any school is greatly hindered by authority — the share of teachers and students that just accept the facts is so high, the people who are interested in understanding the phenomena just get drowned out.

One of the other problem is the ridiculous lack of mathematical prowess. I come from a country that is very famed for it, and I had been complaining about the sad state in my own country. However, now that I am halfway around the world, in a “prestigious” university, I realise how dire the situation it is in the “rich world”. Whereas the number of people who would dare to ask the lecturers is a lot higher, the quality of the questions are really abysmal. 2nd year university physics just should not need to go through quadratic equation, for f*** sake! Luckily, there is always this small pool of die-hard ones who just do so much more than the rest.

One of the reasons that may cause the above 2 problems, and is a humongous problem on its own, is the social pressures. Look at the societal portrayal of Mathematics and Physics. In USA, nonsense such as Fringe is being viewed. Despite the healthy entertainment and curious perspectives, it pays to stick to well known stuff. Feynman would have agreed — he had been telling us all along about the exciting and interesting stuff that we have “completely” known, while the media only focuses upon the latest crackpot idea being proposed. That is clearly not going to foster interest in science.

One way out of this Maths and Physics crisis is to realise that the portrayal itself is damaging. Scott Pilgrim lists Maths as one of the tricky stuff — is it really? Vladimir Arnold managed to teach to Moscow schoolchildren some really advanced topics in Mathematics, and he is not finding it difficult to get good results out of there. And it is definitely not genes / boring rote-learning / other nonsense — he made it a point to specifically root the student in specific examples to flesh out the knowledge.

Which points out another point: Contemporary mathematics is almost disdainful of applications, to the bewilderment of my kind. Pure mathematicians and number theoreticians clearly have reasons and needs for the abstractions, but is it fair to do maths as if it is “abstract, general, and generally useless”? If anything else, maths is clearly the most useful stuff to learn — it is increasingly clear that the progress of mankind is heavily dependent upon the body of mathematical knowledge, of which the “rich world” is losing. Yet, also from the same page in History, we know that mathematical progress tends to hinge itself upon 2 things — physical advancement / requirement and theoretical paradigm shifts, with the first usually happening. If people really understand that maths is, in some sense, a tool to solve problems, it might not be so difficult for them to learn on the job (and we clearly hope they would come to love it despite the loveless start).

Geometry might have to be reintroduced into the mathematical community — the majority of the people on my course, even the respectable few, have, in general, a woeful grasp of geometrical ideas, and hence prefer to work in abstract terms. Sadly, the people who specialise in the abstract tend to completely forget whatever they were working on, and simply just get stuck. If they were mathematicians, that may still be acceptable behaviour, but as a theoretical physicist, being unable to describe the properties of the quantum particle when the wavefunction is completely and perfectly well-plotted in front of you is just disaster waiting to happen. Not to mention: there is no superfluous tool — the moment you need it and you don’t even know about its existence is the same moment you will be condemned to a life of inferiority (Nobel-wise, anyway).

There is also no reason why Maths and Physics cannot be taught in terms of games, for a wide variety of situations. Enough said.

In the big picture, though, the complete lack of education on the point of science and education itself is the _real_ problem. The point of the “scientific method” for all its fallacious existence, is to question authority and teach people to make judgement properly (and yes, improper judgement happens! And we do know of judgement that is a lot better than the nonsense so many people use!). Why do we want education in the first place? The obvious answer is to churn out useful citizens of the world. That is only a nice by-product — the world view brought about by that is more than just disgusting. There are many more reasons that make more sense and have better connotations, and the proof of that should be left to the reader at this point (this post is really too long already).

Many thanks to everyone who responded. This topic seems to have hit a nerve. Good! It should. You’ve given me–and our readers–a lot to think about. More on Friday….

> “explaining […] the methodologies I use in trying to make science accessible to non-specialist readers, and I had been reading passages from my new book to illustrate my points.”

Are these written up somewhere? That could be helpful to others attempting similar communication.

> “I didn’t know that there was anything to be done about physics textbooks”

A remarkable aspect of science education is its power to surprise people with how very much it’s not yet working.

Even people doing science education research. Let alone science education. Let alone science. Let alone anyone else.

> “Afterward, in the hallway outside the auditorium, I talked to the person who had asked the question. A small crowd quickly gathered, and the conversation grew quite animated. The physicists, talking over one another, pressed forward. They wanted me to know, urgently wanted me to understand, that their field is in danger. Physics textbooks, they told me, are a generation out of date. Students aren’t coming out of high school wanting to be physicists. And why don’t they want to be physicists? Because they don’t know—can’t know—what physics is!”

Nice paragraph.

And some fields are even worse. Cell biology has been changing even more rapidly. So its undergraduate material, and even graduate, is also recognized as badly failing to keep up.

> “What can we do about high school physics textbooks?”

One line of response might go like this. Changing the textbooks and curricula of schools, is a dauntingly difficult endeavor. But the students you care about read more than just textbooks. So it’s far easier, and for some purposes sufficient, to create supplementary material. And with open textbooks, and blogs and such, the effort can be spread across a community. Do books like you wish to see currently exist? Do fragments? If not, does at least a characterization of need exist? Then personally, incrementally, contribute to attacking the problem. Recognizing that it’s you, individual members of the scientific community, who are just about the only ones with the motivation and ability to do so. (Lack of) incentives being what they are. Though some NSF funding exists to help. It’s not a happy answer, but…

Thanks for your post.

Thanks for your insightful, thoughtful comments. Great stuff. I really appreciate it. As for your question:

Are these written up somewhere? That could be helpful to others attempting similar communication.

The answer is no. But maybe I should think about it.

Thanks again.