It was a great moment, maybe one of the greatest that any Egyptologist has ever experienced. Peering into the newly breeched tomb of Tutankhamun, Howard Carter gazed in rapture at all the wondrous objects lining the pharaoh’s tomb. There were “strange animals,” he later wrote, “statues and gold–everywhere the glint of gold.” As Carter held out his candle, he was lost in exhilaration, lost in a moment he would never ever live again. But just then the voice of reality intruded. The man behind him was getting a little impatient. “Can you see anything?” the voice inquired.

That voice belonged to Lord Carnarvon, a lover of antiquities whose buckets of money and enviable political connections had allowed Carter to trudge up and down the Valley of the King for five years before finding Tutankhamun’s tomb. Most people tend to forget about Carnarvon, Carter’s generous patron, largely because the British aristocrat died just three months after the great discovery.

But there’s one person who has not forgotten the British aristocrat. Zahi Hawass, the Secretary General of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities has just this week declared war on the Carnarvon family, specifically the current Earl and Countess.  The couple recently opened an exhibition of the old lord’s antiquity collection in their home, Highclere Castle (the principal set of the current PBS series Downton Abbey). And the Countess has just published a book on her family’s Egyptian treasures.

The couple recently opened an exhibition of the old lord’s antiquity collection in their home, Highclere Castle (the principal set of the current PBS series Downton Abbey). And the Countess has just published a book on her family’s Egyptian treasures.

The battle in question is over this collection. Hawass wants it back. Last week in the Arabic daily Asharq Alawsa, the Egyptian researcher noted that Carnarvon initially attempted to negotiate with the Egyptian government for a set percentage of the Tutankhamun finds, a then-common archaeological practice known as partage. (It has since been renounced by archaeologists.) And when that tactic failed, Hawass alleges, Carnarvon attempted to steal some artifacts. All this, he suggests, casts strong suspicion on the origins of the current collection. “The battle between us and the family of Lord Carnarvon has now begun over the return of these antiquities to Egypt, and I do not believe that Lord Carnarvon’s grandson can prove that they were taken from Egypt legally.”

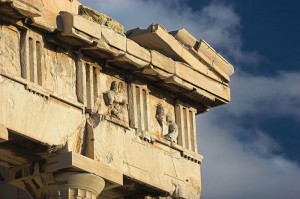

I’ve been following Hawass’s work for many years now. He is a tireless, if sometimes annoying champion of the principle of repatriation–removing ill-gotten antiquities from the collections of major museums and returning them to the country of origin. It’s an idea with great popular appeal. The Greeks, for example, would be overjoyed to see their national treasures, the Parthenon marbles, returned from the British Museum. Indeed, the Greek government has even built a spectacular new museum to house them.

I’ve been following Hawass’s work for many years now. He is a tireless, if sometimes annoying champion of the principle of repatriation–removing ill-gotten antiquities from the collections of major museums and returning them to the country of origin. It’s an idea with great popular appeal. The Greeks, for example, would be overjoyed to see their national treasures, the Parthenon marbles, returned from the British Museum. Indeed, the Greek government has even built a spectacular new museum to house them.

Hawass has enjoyed several successes in his repatriation campaign, and I’d personally like to see all of Tutankhamun’s treasures reunited in one museum in Egypt. The Egyptian government is currently picking up a hefty tab for a $600-million museum under construction near the Giza pyramids in southwestern Cairo: it plans to install the Tutankhamun artifacts as the centerpieces.

It seems to me that Zahi Hawass is now turning the tables on the Carnarvons, becoming the new voice of reality. Times have changed since Howard Carter first peered into Tutanhkamun’s tomb, and the repatriation movement is gaining momentum. Late last fall, after years of legal wrangling, for example, Yale University agreed to give back thousands of artifacts that a wealthy American, Hiram Bingham, excavated from Machu Picchu between 1911 and 1915. Peruvians were overjoyed.

If Hawass has his way, Tutankhamun’s lost treasures will enjoy a similar fate.

Photos: Above. Replica of Tutankhamun’s ritual bed. Photo by Michail. Middle. Highclere Castle. Courtesy JB and UK Planet. Below. The Parthenon’s west metope, sans the Elgin marbles. Courtesy Thermos.

In the last Will and Testament of the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, his wife, Almina, was left ALL the items in the Earl’s Egyptian Collection.

A full narrative about the subsequent disposal of the bulk of the Collection by Almina to America ( and the fate of what was left over i.e. not sold or unwanted or not listed by Howard Carter ) is revealed in my recently completed biography of Almina, the 5th Countess of Carnarvon, who lived until 1969. The book entitled ” The Life and Secrets of Almina Carnarvon” is available from me, in the UK.