As a journalist, I live in constant terror of making mistakes. This anxiety typically simmers just below the surface of my consciousness, occasionally bubbling up to grab me in a full choke hold. But errors are more or less inevitable in this business. And last week, I made one.

As a journalist, I live in constant terror of making mistakes. This anxiety typically simmers just below the surface of my consciousness, occasionally bubbling up to grab me in a full choke hold. But errors are more or less inevitable in this business. And last week, I made one.

A new Nature study showed that the metal bands scientists put on penguins’ flippers to track them are bad for the birds. The authors reported that banded birds had 39% fewer chicks and a 16% lower survival rate than unbanded birds over ten years. (Why would this be? The bands seem to create drag when the penguins swim, which means they must work harder to go the same distance as their unbanded counterparts.)

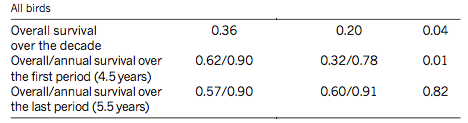

When I covered the research for ScienceNOW, I used those figures. Here’s the problem: If you glance at the table where the study’s authors report overall survival, you’ll find that the survival for unbanded penguins was 0.36 and survival for banded penguins was 0.20 (that is, the number of birds present at the end of the study divided by the number of birds present at the beginning). That’s actually a drop of 44 percent, or 16 percentage points. (Don’t understand the difference? Join the club. There’s a nice explanation here and here.)

Eagle-eyed Seth Borenstein, a veteran environmental reporter for Associated Press, caught the error, called the authors to confirm, and then made a list of 14 journalists who used the 16% figure — in other words, those of us who got it wrong. And presumably he sent that list to Charlie Petit, who runs Knight Science Journalism Tracker. “Do the math. Most journos didn’t,” reads the headline of Petit’s post.

I’m number two on Borenstein’s list. And Petit added this comment: “Boy, did Science miss a chance to tweak Nature on this one!” Never mind that I’m a freelancer who writes for both publications and wouldn’t care to “tweak” one to benefit the other even if I had caught the error.

It’s never fun to be singled out for something you did wrong. And it’s especially painful when you’re made to feel like you don’t know how to do your job. Initially, I felt terrible about making this mistake. But over the past week, I’ve come to terms with it. Yes, I reported 16%. So did the researchers and at least 13 of my colleagues. The peer reviewers didn’t catch the error, and neither did the Nature employee who wrote the press release.

According to Petit’s list, only three journalists “got it right,” including a woman whose story appeared on carrentals.com. But in truth only one journo reported 44% lower survival: Borenstein. The other two got credit for reporting 40%, but they were referring to the percentage drop in chicks, not survival.

Still, the whole mess has made me question whether I understand my job description. Should I have caught that mistake? Should I take a statistics class? Bone up on my math skills? Do I need to carefully comb through the tables and charts in every paper looking for oddities? I try to be a careful reporter. Am I failing?

I doubt Borenstein’s goal was to make me feel bad. I’m sure he viewed this as a teachable moment. And I did learn a valuable lesson about the difference between percentage and percentage points (wait, explain the difference to me again). Nevertheless, the anxiety is back full throttle. Last night I had a dream I was playing Tetris. But it wasn’t random shapes that were falling, it was words. And I had to arrange them to make a story. At least they weren’t numbers.

Claire Saraux, one of the study’s authors, says the mistake wasn’t so much a mistake as it was a miscommunication. In a comment on Petit’s post, she explains that she and her colleagues meant to use the more conservative 16% figure. Now they know they should have written 16 percentage points. She writes, “We apologize for any misunderstanding (note that whereas scientific press is English, it is not the native language of a number of authors, who endeavour to write studies as clearly as possible).”

Image credit: Nick Russill on flickr

Looking at the list of others who got it wrong, you’re in quite good company, Cassie!

I feel like….we’re supposed to report on what the researchers tell us, and what other independent researchers say about a study. If none of those people catches the mistake, and the damned journal editors don’t catch it, then you can’t feel too bad about missing it, too. Kudos to Borenstein, who is clearly very proud.

Fear of mistakes is probably the worst part of our job, but probably also keeps us at the top of our game. And taking a thoughtful look at our mistakes, as you’ve done here, is brave and admirable.

Typical–the researchers missed it, the journal editors missed it, the independent researchers missed it–and the journalist who reported the study gets the blame.

On the mistake itself, I noticed it and just ended up quoting the actual 20% and 36% figures. Readers can see for themselves the gulf between them.

BUT, I think this is a bit of a hullaballoo over an area where there’s no clear right answer. Yes, percentage points and percentages are a bit different but try asking your readers what the difference is. We write for our audiences, right? Well our audiences are pretty bloody confused. Say survival rates fell by 44% and many will hear percentage points. This is why I think it’s best to quote the absolute figures.

Anyhoo, it’s great that you’re written this post in the first place. As Ivan Oransky said on Twitter, you get top marks for transparency. There’s nothing wrong with making mistakes and fessing up to them and engaging with your critics – indeed, these qualities will define the future of science journalism and those who possess them will thrive at the expense of those who dig their heels in. So good on you Cassie. It’s in the nature of our profession that we will make mistakes. And often. And we will get called on it. I say, bring it on. It will make us stronger.

And @Dirk – so what? We’re meant to be the final filter, the last bulwark standing between the public and misinformation. Even if every single person ahead of us on the chain – the scientists, the peer reviewers, the editors, the press officers etc. – make a mistake, we should be the ones who spot it. IF that seems like an impossibly high standard, well I think it’s the one we should set for ourselves.

The constant terror of making mistakes is the science journalist’s unavoidable lot and probably our greatest safety net–lose it, and you might as well drop your Eurekalert subscription and close down your Twitter account. We all make gaffes from time to time, and it’s good to be called to account for them–bracing, embarrassing, but good.

Still, it’s important to keep things in perspective. @Ed makes the point well–we should all strive not to flub even poorly understood/explained statistical terminology, and to avoid that responsibility is to embrace stenography. But this is a different order of error than getting the direction and rough scale of change wrong–or not checking whether that vaccines-and-autism correlation holds up, for that matter.

Anyway, this was gracefully and helpfully handled, Cassandra. Owning mistakes is even more important than fearing them, I suspect. For the record, I once mistakenly referred to a hadrosaur as a sauropod in print–every five-year-old knows the difference. Not the most serious mistake I’ve ever made, by a long shot. But I’m haunted by it to this day. How about the rest of you? The confessional is wide open!

Since moving into the fast-paced, editor-less world of blogging, I wake up in the middle of the night panicked about possible mistakes. I think it’s particularly stressful in science journalism.

Kudos for a thoughtful post that turned an oversight into something positive.

Brave post. I can’t help thinking that if it were me, I’d have had an easy time writing the post, but a very hard time hitting “publish.”

Ed makes a great point about using numbers that easy to understand for readers — even if it means pestering scientists to get out of their usual stats habits to make a straightforward statement in English.

Glad you did put this out in the world. I’ll take up Tom’s challenge and fess up as well. I’ve made my share of mistakes, including sources’ names (feel particularly bad about one doc who shared her doubts with me and made my story) and drug names (me, a pharmacologist by training).

My most embarrassing by far is calling Istanbul the capital of Turkey. None of the editors, subeditors or copy editors caught it. GAH.

I agree with Ed. While I think journalists should understand the difference between percentages and percentage points, there’s not much point being pernickety about it if your readers don’t.

In this case, I think the most effective way to present the data is not in percentages at all but raw numbers e.g. “the researchers compared 50 penguins with bands and 50 without. 10 of the penguins without bands died within the study period, while 18 of the banded birds did.” That’s more vivid, and giving the sample size also gives an idea of the significance of the number.

Thanks for all these helpful comments. I agree that giving the actual numbers would have been far more helpful than what I did, which was lazily use the numbers the researchers gave me. Lesson learned. It’s easy when you do daily reporting to become a reporter automaton, so this is a nice wake-up call.

And, Martin, thanks again for all the nice statistics/math links you posted on the KSJ Tracker penguin post.

Thanks for a great post that made me think. I have to admit I’ve reported numbers that I didn’t completely understand, even after questioning the researchers about them, and I’ve also wondered whether I need to take a statistics class. Your willingness to talk about this will only help make science reporting better.

Cassandra, it’s telling that Knight Science Journalism Tracker was so eager to assist Seth Borenstein in his attempt to discredit science journalists who are reporting on the environment. FWIW, I just posted the following comment to Charles Petit’s original post:

Too bad Seth Borenstein, of the ubiquitous AP, wasn’t doggedly critical in his reporting on the Gulf oil spill. Over the past few months, Borenstein wrote a number of widely disseminated, remarkably ‘credulous’ stories, uncritically reiterating happy talk about the alleged efficacy of dispersants and oil-eating microbes. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/SETH+BORENSTEIN-a11079

Sorry, but I’m not willing to give Borenstein any cred for going all gonzo on reporters who didn’t “do their math” on this penguin study. Let’s see what he does again when there’s a lot more at stake.