A few years ago, a colleague and I hired a cab to journey across the Sahara Desert, from a tiny oasis town to Luxor in the Nile Valley. Before we could head out, however, the driver insisted that we anoint ourselves with perfume he brought for the occasion–a ritual cleansing to protect us from evil spirits and the perils of our journey, the most likely of which was engine trouble. When we finally pulled into Luxor 12 hours later, the three of us were parched and coated head to toe in dust. As I rehydrated in a hotel bathtub, I felt like Lazarus rising from the dead.

A few years ago, a colleague and I hired a cab to journey across the Sahara Desert, from a tiny oasis town to Luxor in the Nile Valley. Before we could head out, however, the driver insisted that we anoint ourselves with perfume he brought for the occasion–a ritual cleansing to protect us from evil spirits and the perils of our journey, the most likely of which was engine trouble. When we finally pulled into Luxor 12 hours later, the three of us were parched and coated head to toe in dust. As I rehydrated in a hotel bathtub, I felt like Lazarus rising from the dead.

Even today, in the age of the internal combustion engine, a Sahara crossing is not to be taken lightly. So it’s no wonder that archaeologists have long dismissed the possibility that our ancient ancestors–early modern humans–ventured successfully across the Sahara more than 100,000 years ago, as they journeyed out of their southern homeland. The Nile Valley seemed a much easier route.

But new research strongly suggests that the Sahara would have been a land of earthly delights for early Homo sapiens.

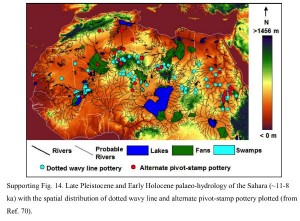

A team of geographers and earth scientists, led by King’s College London geographer Nick Drake, has just studied satellite images of the Sahara and analyzed the distribution of African fish and snail species. What they found was a lush waterworld of Saharan lakes, rivers and swamps (click on the photo to the left to enlarge) that formed during wet intervals in the past. Capitalizing on this climate change, catfish, freshwater snails and at least 23 other animal species migrated north across the Sahara along now vanished watercourses.

A team of geographers and earth scientists, led by King’s College London geographer Nick Drake, has just studied satellite images of the Sahara and analyzed the distribution of African fish and snail species. What they found was a lush waterworld of Saharan lakes, rivers and swamps (click on the photo to the left to enlarge) that formed during wet intervals in the past. Capitalizing on this climate change, catfish, freshwater snails and at least 23 other animal species migrated north across the Sahara along now vanished watercourses.

And where fish and snails ventured, ancient humans may have followed. Drake and his team think that a particularly humid period dated to 125,000 years ago could well have greened and watered the Sahara, forming “dispersal routes at a likely time for the migration of modern humans out of Africa.”

But this possibility raises several questions. Were our early ancestors even interested in the water? Were they swimmers, waders, rafters and fishers? Or did they prefer to stick to good old terra firma? A lot of recent evidence points to the former. In South Africa, for example, archaeologists are working on a 164,000-year-old site known as Pinnacle Point. There early Homo sapiens feasted on brown mussels, a type of shellfish only exposed in large numbers during exceptionally low tides. These tides occur just twice each lunar phase.

“People think that shellfish are easy to capture,” Pinnacle Point archaeologist Curtis Marean told me recently. “But it’s not that way at all. There are optimal times to get shellfish, and going into the water when it’s roaring in the intertidal zone can easily be fatal.”

Other evidence suggests that our ancestors paid close attention to local rivers. In what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, Smithsonian archaeologist John Yellen excavated the site of Katanda along the banks of the Semliki River. There Yellan and his team recovered both elaborate barbed harpoons and the bones of giant Nile catfish, all dated to at least 80,000 years ago. It now looks as if early Homo sapiens timed their visit to Katanda to coincide with the catfish spawning season, when the huge fish assembled in great numbers and could be taken easily by harpoon.

For such aquatic hunters, a new waterworld in the Sahara would have been difficult to resist. And as I sit here, I am imagining them moseying up those now vanished watercourses in simple dugouts and rafts–watercraft that may later have ferried them out of Africa and along the coast of Asia. Maybe, just maybe, an early, abiding love of water was the key to our rapid colonization of the world.

For such aquatic hunters, a new waterworld in the Sahara would have been difficult to resist. And as I sit here, I am imagining them moseying up those now vanished watercourses in simple dugouts and rafts–watercraft that may later have ferried them out of Africa and along the coast of Asia. Maybe, just maybe, an early, abiding love of water was the key to our rapid colonization of the world.

Photos: Solomon Dugout Canoe from below, courtesy mjwinoz. Map of Lush Sahara, courtesy Nick Drake. Drop of water falling from a piece of ice, courtesy Jonas Bergsten.

Sir,

The much preferred route of Out of Africa migration of Homo Sapiens, for all archeologists and DNA scientists is ‘beachcomber route’ till Australia. And with that this route through Sahara is also competing. Why nobody wants the Nile route? Also the reason for migration is given as the dry climate during the glacial period when all the water bodies have frozen and in the dry spell there was not enough food for all. In that case is not the central African region which could be warmer since it is in the equatorial zone. What advantage the primitive human being can get if he moves North? From where can I get an answer for these?