The last Zooniverse project I spent time on was also their first, Galaxy Zoo 1. You looked at pictures of galaxies and decided whether they were shaped like spirals or ellipticals. I could do that, it was fun, and better yet, it was citizen science, 350,000 citizens doing real science with real scientific results, so I wrote about it a lot. A few days ago, the Zooniverse sent me a little message saying Woo! New project! Find a planet around another star! Test your eye and brain against a computer! I think: Bring it on. I log into the Zooniverse.

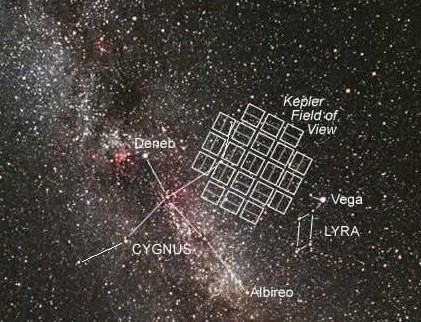

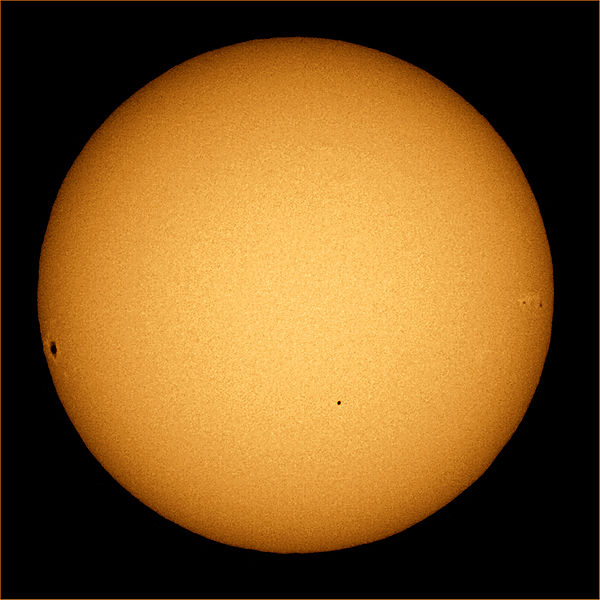

First I read “About:” NASA’s Kepler satellite has been looking at the same part of the sky some time now, effectively making a movie of all the stars. Some stars dim and brighten for their own internal reasons; others dim and brighten because one of their planets moves in front of them, temporarily blocking their light. The Kepler people have computers to sort out regular variability from planet-induced variability, which is hard because the measurements have noise in them. Humans, however, are good at looking at noise and finding patterns. So the Kepler people made a month’s worth of data public and put it in the Zooniverse. The Zooniverse is betting that their citizen scientists will find more planets than Kepler’s computers do.

First I read “About:” NASA’s Kepler satellite has been looking at the same part of the sky some time now, effectively making a movie of all the stars. Some stars dim and brighten for their own internal reasons; others dim and brighten because one of their planets moves in front of them, temporarily blocking their light. The Kepler people have computers to sort out regular variability from planet-induced variability, which is hard because the measurements have noise in them. Humans, however, are good at looking at noise and finding patterns. So the Kepler people made a month’s worth of data public and put it in the Zooniverse. The Zooniverse is betting that their citizen scientists will find more planets than Kepler’s computers do.

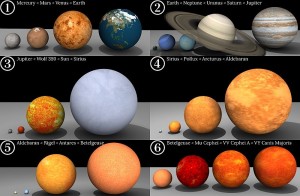

First I do a test. I’m given a little snowstorm that meanders across a graph and am to find the snowflakes that fall off the meander in a straight line. I do splendidly. Now, the real thing: a dwarf star, o.6 times the radius of the sun, apparent magnitude (how bright it looks) is 15.3 (visible but not overly so). I figure out that the snowstorm is all the measurements of the star’s magnitude — 15.4, 15.9, 15.1, etc., I’m making those numbers up. Belatedly I look at the labels on the graph; I don’t quite understand them so I’m going to pretend they’re brightnesses versus time, Day 1 through Day 35. So the straight line of snowflake magnitudes are those times when the star’s brightness drops because a planet’s in front of it. Or something like that anyway. I see maybe one straight line of snowflakes — if two points and a mess make a straight line. I have no confidence in my assessment and feel correspondingly stupid. I accept stupidity and move on. Click.

Next: dwarf, 0.9 sol, magnitude 14.2, and by golly! I see snowflakes falling in a line! Seven lines! Seven times around the star! I mark them! I reflect: The planet is orbiting a star about the size of the sun, seven times in 35 days. We orbit ours once in 365. That’s some zippy planet. I lose confidence again. Nevertheless, I click. Next: giant, 3 sols, magnitude 11.7, a big bright guy. I find three lines and oh no, this one was a simulation so I learn the star’s truth and it does have three lines but only one of them was one I saw. I bravely learn from mistakes. Click, next: giant, 9.1 sol, magnitude 13.2. Six snowflake lines, six times in 35 days and around a giant star? Damn my human pattern-finding abilities, damn them! They’re going to kick me out of citizen science.

Next: dwarf, 0.9 sol, magnitude 14.2, and by golly! I see snowflakes falling in a line! Seven lines! Seven times around the star! I mark them! I reflect: The planet is orbiting a star about the size of the sun, seven times in 35 days. We orbit ours once in 365. That’s some zippy planet. I lose confidence again. Nevertheless, I click. Next: giant, 3 sols, magnitude 11.7, a big bright guy. I find three lines and oh no, this one was a simulation so I learn the star’s truth and it does have three lines but only one of them was one I saw. I bravely learn from mistakes. Click, next: giant, 9.1 sol, magnitude 13.2. Six snowflake lines, six times in 35 days and around a giant star? Damn my human pattern-finding abilities, damn them! They’re going to kick me out of citizen science.

I seek company for my misery in the “Discussions” where citizens ask questions and real scientists answer. The citizens are wondering whether a star that jumps all up and down the brightness axis of the graph is probably a variable. Smart citizens. A scientist writes that planets with four-day orbits are close to their stars, which will dim every four days.

I do the higher math: six times in 35 days = once around the star everysix days or so. I could have been right! I’m starting to feel smart myself. As is citizen scientist, Uncle Clover: I see all sorts of things in these light curves, he writes. I look at the curves, and I see the star system. I didn’t even know my mind would do that, but it seems to do it naturally. I’d love to train this skill to put it to good use.

Ok! There’s the ticket! Let’s train this skill and put it to good use. We have planets to find and no computer is a match for us. We are The Planethunters!

Photo credits:

Sun from Mars: NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover

Kepler’s star field: Carter Roberts / Eastbay Astronomical Society.

Planet/star sizes: Dave Jarvis

Transit of Mercury: Mila Zinkova