Each year by this date I’m pretty much done with Christmas carols. Few powers on earth could force me to listen one more time to Mel Torme’s The Christmas Song or the Pogues’ Fairytale of New York, superb as these recordings are. But despite all this frying of the synapses by cold, relentless, commercial repetition, there’s still one carol that can still spirit me away to the joy of the season: We Three Kings of Orient Are. The music is gorgeous; the lyrics wonderfully simple. “Bearing gifts we traverse afar/Field and fountain, moor and mountain/Following yonder star.”

Each year by this date I’m pretty much done with Christmas carols. Few powers on earth could force me to listen one more time to Mel Torme’s The Christmas Song or the Pogues’ Fairytale of New York, superb as these recordings are. But despite all this frying of the synapses by cold, relentless, commercial repetition, there’s still one carol that can still spirit me away to the joy of the season: We Three Kings of Orient Are. The music is gorgeous; the lyrics wonderfully simple. “Bearing gifts we traverse afar/Field and fountain, moor and mountain/Following yonder star.”

The songwriter, John Henry Hopkins Jr., an Episcopalian deacon tending his flock in New York City in 1857, was clearly a man of his times, and the carol he wrote perfectly conjures up the spirit of adventure and exploration that pervaded the Victorian era. But the story of the Magi is, of course, a very old one, from the Gospel of Matthew. And it has long intrigued archaeologists–particularly the description of the gifts.

Frankincense and myrrh are aromatic tree resins collected even today along the Horn of Africa and southern Arabia by farmers and pastoralists. So sweet and pungent is their fragrance that priests across the ancient world coveted them as incense for their temples. Egyptian queens traced thick black lines along their eyes with charred frankincense known as kohl. And Egyptian embalmers sealed the bodies of their wealthiest clients with a resin made of three compounds–camphor oil, juniper oil and myrrh.

The unique properties of this embalmer’s resin greatly surprised a team of researchers led by American epidemiologist Aidan Cockburn in the 1970s. The team took samples from a mummy at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, and later marveled that the ingredients had melded together and polymerized to “form a vast and continuously molecular form” –rather resembling organic glass. Cockburn and his colleagues could not refrain from a rather poetic comment about this resin and its properties “Embedded in glass, as it were,” they wrote in their final report, “there is no reason why the body, as long as it is kept in a warm, dry or cold place should not survive until the end of time.”

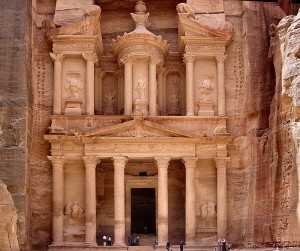

Such coveted commodities soon sparked a major international trade. Arabian merchants dispatched heavy packs brimming with frankincense and myrrh by camel trains lumbering westward along Middle Eastern caravan routes. And pastoralists in Jordan came up with a very clever idea: taxing all caravans that entered their territory. The immense wealth they reaped from the frankincense trade in the 1st and 2nd century financed some of the most exuberant architecture of the ancient world–the glories of Petra.

But I digress. It seems to me that three Magi could not have chosen better gifts for their journey westward. Gold, frankincense and myrrh would never have gone amiss as a present.

Photos: Upper is Detail from The Adoration of the Magi, a tapestry designed by Edward Burne-Jones. Middle is frankincense resin, by Peter Presslein. Lower is The “Treasury” at Petra by Markv