In the summer of 1993, just weeks before bulldozers began rolling in for the largest transportation project in Boston’s history–the Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel–archaeologists discovered what appeared to be two 19th century privies and a cistern along the old waterfront. Unable to come up with funding to dig them, Boston archaeologist Martin Dudek and his colleagues decided to excavate the sites on their own time, recovering nearly 3000 artifacts, from leather shoes and cosmetic jars to a host of imposing looking syringes.

In the summer of 1993, just weeks before bulldozers began rolling in for the largest transportation project in Boston’s history–the Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel–archaeologists discovered what appeared to be two 19th century privies and a cistern along the old waterfront. Unable to come up with funding to dig them, Boston archaeologist Martin Dudek and his colleagues decided to excavate the sites on their own time, recovering nearly 3000 artifacts, from leather shoes and cosmetic jars to a host of imposing looking syringes.

It now turns out that the privies and cistern belonged to a thriving Victorian-era brothel. In an ongoing research project, Boston University archaeologist Mary Beaudry and her students are now analyzing the artifacts, combing old census records and other documents, and shedding new light on the lives of the women at 27 and 29 Endicott Street.

Historical archaeologists have taken quite an interest in old brothels in recent years. Not far from the White House, for example, archaeologist Donna Seifert excavated several 19th-century Washington brothels that catered to a very upscale clientele–largely politicians. These establishments boasted flower pots, expensive lighting, steak dinners and ample supplies of champagne, and their inhabitants sported fine clothes with fancy glass buttons. Such brothels, concluded Seifert, offered poor working-class women a shot at a middle-class life, complete with fine cuisine.

Historical archaeologists have taken quite an interest in old brothels in recent years. Not far from the White House, for example, archaeologist Donna Seifert excavated several 19th-century Washington brothels that catered to a very upscale clientele–largely politicians. These establishments boasted flower pots, expensive lighting, steak dinners and ample supplies of champagne, and their inhabitants sported fine clothes with fancy glass buttons. Such brothels, concluded Seifert, offered poor working-class women a shot at a middle-class life, complete with fine cuisine.

But this, of course, was the top drawer of the Victorian sex trade. Far below were the “nightbirds,” older women–many infected with sexually transmitted diseases–who waited in dark alleys for their clients, then took them back to basement rooms known as cribs.

The brothels on Endicott Street, however, fell somewhere in between. Student Amanda Johnson discovered in her analysis of census records from the era that the workers were young–25 years of age or less–and generally came from farm or immigrant families. Moreover, they faced stiff competition. In 1851, 227 houses of ill repute welcomed clients in Boston.

Endicott Street’s madam, a certain Mrs Lake, was not one to give up easily. In 1867, she rented a room in one of her establishments to a Boston policeman, who may have helped protect the women from rough trade. And that year, Mrs Lake took a new husband–Dr. William Padelford, a physician who moved into 29 Endicott Street where he carried on a homeopathic medical practice. Quite likely it was Padelford who provided all the imposing looking syringes that archaeologists found in the privy.

What was the basis for the marriage–love or profit? Beaudry and her students are continuing to pore over old public records as well as the artifacts from the dig. But already Beaudry has detected a faint whiff of gentrification at the two brothels. The residents possessed a large tea set and an ample supply of dinner ware, enough to serve their clientele a respectable meal and give the impression of a refined house–something that more downmarket establishments could never manage.

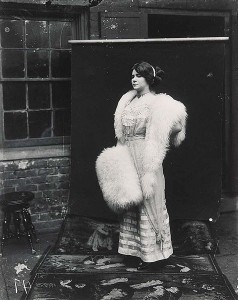

Upper photo: Image of Storyville prostitute, by E. J. Bellocq, circa 1912. “Storyville Girl Posing Out of Doors” with backdrop. Courtesy Wikimedia commons.

Lower Image: “Woman in a Brothel” by Henri De Toulouse_Lautrec. Courtesy www.toulouse-lautrec-foundation.org

Prostitutes, politicians and the illicit drug trade seem to have been endemic across the continent during the Victorian era.

Here’s a similar story from the west coast, penned by another very talented writer!

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/british-columbia/tom-hawthorn/victorias-colourful-history-of-sex-for-sale/article1774028/

Hey Dan:

Thanks very much for pointing us to this link. Very cool article!