The procedure, developed in the late ’50s, is called fecal transplantation. Those of you who watch Grey’s Anatomy will have heard of it. And, yes, it is what you think it is. A physician takes poop from one person, and then he puts it into another. Don’t worry. The recipient doesn’t have to swallow the donor’s feces (an act that might put a positive spin on the phrase ‘eat my sh*t’). Blessedly, it goes in through the rectum instead.

“Why, for God’s sake why!?” you ask. Well, I’ll tell you. Poop is teeming with microbes. The typical human gut houses trillions of bacteria — more bacteria than the human body has cells. Together they form the gut’s “microbiome.” These bugs keep you happy and healthy. They aid in digestion, immunity, and much more.

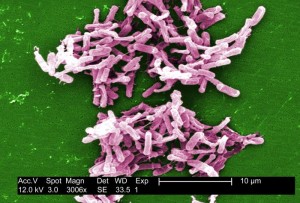

Antibiotics, however, can throw a wrench in this delicate ecosystem. When so-called “good” bacteria die, gut-wrenching, diarrhea-causing “bad” bacteria can take over. Clostridium difficile, which causes cramping, a fever, and the runs, is a particularly nasty bug. But researchers have found that if you put feces from a healthy person into the colon of someone with a C. difficile infection, the good bacteria will wipe out the bad.

The September issue of the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology contained three articles on the fecal microbiome. One paper showed that the effects of a fecal transplant are lasting. The researchers gave 19 people suffering from C. difficile infection fecal transplants. All 19 were cured. And the cure seemed to last for up to four years (although three patients apparently became reinfected after taking antibiotics for another illness).

In an accompanying editorial, gastroenterologist Martin Floch writes, “Although there are still some skeptics, it is clear from all of these reports that fecal bacteriotherapy using donor stool has arrived as a successful therapy.” He adds, however, “Probably one of the major problems is to define how this therapy can become socially accepted. (Can you imagine the Food & Drug Administration discussion?).”

Fecal transplants have been largely reserved for particularly difficult cases of C. difficile infection that don’t respond to other treatments. In an article published yesterday in The Scientist, Cristina Luiggi points out that the therapy may hold promise for other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease and perhaps even obesity.

Of course, targeted microbial therapies are likely a long way off. Scientists still don’t fully understand how the human microbiome influences our health. But the National Institutes of Health has been working to change that. In 2008, NIH launched a $157 millon project to plumb the human body’s nooks and crannies for microbes and sequence their genomes. The Human Microbiome Project “has the potential to transform the ways we understand human health and prevent, diagnose and treat a wide range of conditions,” said former NIH Director Elias A. Zerhouni in a 2007 press release. In May, researchers published the first collection of bacterial genomes – 178 in all. NIH hopes to eventually have 900 microbial genomes to add to its reference collection.

**

Science writer Carl Zimmer had an excellent article about fecal transplants in the New York Times in July. Read it here.

Photo credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention