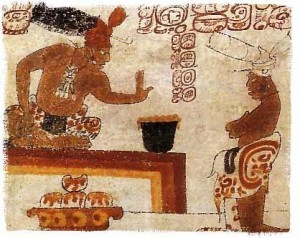

In the early 8th century A.D., the great Maya city state of Tikal reached the zenith of its sophistication and power. Its kings sipped frothy chocolate and smoked elegant cigars in their chambers, listening to the music of trumpeters and drummers. Its painters rendered brilliant court scenes on vases. Its architects designed pyramidal masterpieces that climbed to the sky. Tikal was the Manhattan of its day.

Over the next century and a half, however, the bloom went off the rose in Tikal. Its ambitious building program collapsed and its artists ceased to carve inscriptions on stone. Its divine kings vanished and its population thinned to just 20 percent of its peak. Tikal, moreover, was not the only Maya city state to suffer such a dramatic fall from grace. Elsewhere in the Maya world, dozens of other splendid cities crumbled over a span of 300 years ending around A.D. 1050.

Archaeologists have pointed to many reasons for the fall of the classic Maya civilization. The Maya slashed and burned most of their forests. They mined the fertility of their fields and allowed their populations to soar unchecked, straining food supplies. Then they fought wars over prized resources, terrible wars. When climate change finally arrived in the 8th century, in the form of severe, prolonged droughts, many Maya were singularly ill-equipped to weather it.

Just how did the Maya react to this sudden disastrous change in climate?

According to recent research by Holley Moyes, an archaeologist at the University of California in Merced, Maya kings and their ritualists placed the ancient equivalent of 911 calls–to the Maya god of rain.

In Classic times, the Maya believed that a cave-dwelling deity named Chac created cloudbursts by pouring water from an overturned jar. To win Chac’s favor, Maya kings and their shamans often journeyed to caves to perform sacred ceremonies, and it is not too much of a simplification to say that the power of Maya kings came largely from their success as rainmakers. As long as the annual rainy seasons returned and the cornfields prospered, Maya kings ruled as gods over their subjects

Moyes studied leftovers from the rituals held in Chechem Ha Cave in Belize. What the archaeologist discovered was a major change in the rituals around A.D. 680—just as serious climate change was beginning to afflict the region. Before 680, when conditions were relatively wet, ritualists had circled and danced around a giant icicle-like stalactite that hung from the ceiling; then they left a few broken pieces of painted pottery behind as gifts for Chac.

Moyes studied leftovers from the rituals held in Chechem Ha Cave in Belize. What the archaeologist discovered was a major change in the rituals around A.D. 680—just as serious climate change was beginning to afflict the region. Before 680, when conditions were relatively wet, ritualists had circled and danced around a giant icicle-like stalactite that hung from the ceiling; then they left a few broken pieces of painted pottery behind as gifts for Chac.

But after 680, Maya ritualists hauled whole pots into the cave—no easy matter in the winding darkness—and stowed them on every possible surface. They leaned them against remote back walls and stacked them one on top of another on high ledges that would have been very hard to reach. And their offerings generally took a specific form—large, wide-mouthed jars designed for collecting and storing water. “These jars are what rain deities use,” Moyes told me when I talked to her. “So this is the perfect gift.” Sometimes the ritualists left them upside down on the ground, simulating the act of pouring, and they made sure that the pots could hold a lot of water. Some jars were so large that a human could nestle comfortably inside.

One can clearly see the desperation—nigh on panic—that gave rise to these later rituals. But the rain god did not come to the assistance of the Maya supplicants. The countryside around Chechem Ha suffered through a 44-year-long dry spell in the late 8th century, and after that, few Maya worth their salt likely believed that their kings were capable of making rain. At Minanhá, a Maya urban center very close to Chechem Ha, inhabitants either deposed their king or allowed him to step down of his own free will.

Then they proceeded to obliterate all physical trace of him. After that, there were no more urgent appeals to Chac.

Our government should read this article…

History does repeat itself when one does not

learn from history. Sallie