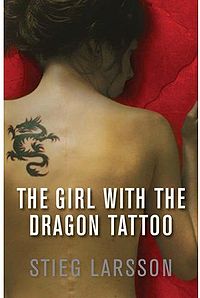

Like millions of other readers I’ve turned into a couch potato this summer, curled up with Stieg Larsson’s addictive page-turners. I could be out accompanying my dog Max as he tears through his favorite park hunting for forgotten sandwiches on summer evenings. Or dallying on the beach with g&t in hand. But no. I’m at home, mastering the intricacies of Swedish geography, intelligence agencies, and libel law. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has shanghaied my summer.

Like millions of other readers I’ve turned into a couch potato this summer, curled up with Stieg Larsson’s addictive page-turners. I could be out accompanying my dog Max as he tears through his favorite park hunting for forgotten sandwiches on summer evenings. Or dallying on the beach with g&t in hand. But no. I’m at home, mastering the intricacies of Swedish geography, intelligence agencies, and libel law. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has shanghaied my summer.

I’ve now finished the third and final book in Larsson’s trilogy, a strapping doorstopper at 563 pages in hardback. The series was a great read, and almost worth all those forsaken summer pleasures. But on one point, I am miffed. Larsson never tells us why his hacker heroine, Lisbeth Salander, has that famous dragon tattoo breathing fire across her back.

Sure, she’s about as volatile a character as I can recall in fiction, a kind of dragon lady in Goth. And it may be that Larsson simply intended to remind us of the extreme consequences that awaited anyone who messed with Salander. But since the Swedish author died soon after submitting all three novels to his publisher, we will never know. And that leaves a huge, open field for speculation.

So I began thinking about this famous tattoo, and then tattoos in general. And since I’m an archaeology writer, I began thinking about body markings in an archaeological way. Who, I wondered, were the first people to sport images on their bodies and why? And what did the ur-tattoos look like? Some of the answers surprised me.

The world’s earliest known tattoos adorn the body of a 5,300-year-old man, dubbed Oetzi, who melted out of a glacier in the Tyrolean Alps in September 1991. Oetzi had not just one tattoo, but an entire collection of them, 57 in all. They are pretty simple affairs–cross-shaped markings on his right knee and left ankle, and several groups of parallel lines on other parts of his body. All are dark-blue in color.

An Austrian-Italian scientific team, led by University of Graz cell biologist Maria Ann Pabst, examined several of these tattoos by optical microscopy and other related techniques last year. Pabst discovered that the iceman’s tattoos contained minute traces of soot and tiny quartz and garnet crystals–all likely swept up from an ancient hearth. “I can imagine that [the tattooists] used some pointed material, maybe thorns, and dipped it into the soot,” she told Discovery News, “and then pierced into the skin, or made scars, and put soot into the wound after insertion.”

Now here’s the part that surprised me. Pabst and others now suggest that the iceman acquired his tattoos from an acupuncturist. According to a report published in the British medical journal, The Lancet, in 1999, “three [modern] acupuncture societies indicate that nine of the tattoos could be identified as being located directly on or within 6 mm of traditional acupuncture points.”

Now here’s the part that surprised me. Pabst and others now suggest that the iceman acquired his tattoos from an acupuncturist. According to a report published in the British medical journal, The Lancet, in 1999, “three [modern] acupuncture societies indicate that nine of the tattoos could be identified as being located directly on or within 6 mm of traditional acupuncture points.”

The ancient man had his reasons for seeking medical help: His hips, knees, ankles, and lumbar spine were all degenerating painfully. To help such patients today, acupuncturists target several of the same anatomical points. These findings, concluded The Lancet report, “provide strong evidence that a form of medical therapeutics, very similar to what we know as Chinese acupuncture, was already in practice 5200 years ago in Central Europe.”

It’s an interesting thought. Perhaps Chinese acupuncture draws on a far more ancient tradition of healing than previously thought. And maybe there was something more to Lisbeth Salander’s tattoo than meets the eye, too.