It’s one of the pitfalls of science journalism: Assigned a story, we rush madly off, interviewing scientists galore, gathering mountains of eclectic facts we’re sure our readers will love. Alas, it’s often impossible to cram all these facts on the printed page, because magazines have space constraints. C’est la vie. But hey, this is the blogosphere, where lost facts come to life again.

So here are some of the odd stories that I unearthed when researching The 12 Dirtiest Fruits and Vegetables, published in the August 2010 issue of Prevention magazine. The feature describes the Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides, produced by the Environmental Working Group. The Guide lists a “dirty dozen” of 12 fruits and vegetables with the highest pesticide residues (as determined by U.S. Department of Agriculture tests) and a “clean 15” of less-contaminated produce. (In fact, many of the items on the “clean 15” list are heavily sprayed, but are peeled before they are tested or eaten, so residues are lower.) Weird fruit-and-veggie facts follow:

1. The fat juicy strawberries we know and love arose by accident in 18th century Europe—as a random cross between two imported native American species: one hardy and bountiful, the other a producer of big dangling fruit. The new plant, “a mutant freak,” with eight sets of chromosomes (also known as an “octoploid”) combined both traits, making its sweet fruit both very valuable and very vulnerable to pests and pathogens. In 2008, farmers in California applied 9,826,310 pounds of pesticides to their strawberry fields, including fumigants designed to sterilize the soil and kill all microorganisms.

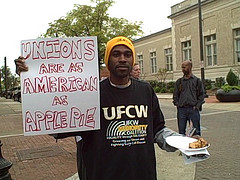

2. There’s nothing less American than apple pie: As Michael Pollan reveals in his fascinating book, The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s Eye View of the World, the wild ancestors of apples arose in Kazakhstan in Central Asia. Legendary vagabond Johnny Appleseed, aka John Chapman, carried apple seeds across the U.S., which grew into trees that sprouted fruit “sour enough to set a squirrel’s teeth on edge,” according to Henry David Thoreau. Enterprising orchard-tenders later selected the sweetest, hardiest or reddest apples and grafted them to produce identical clones. Unlike seeds, which are the product of sexual reproduction, clones do not mix up their genes (which is how species evolve resistance to disease and pests) and so common varieties of apples, such as Red Delicious, are susceptible to a wide range of ever-adaptable insects, viruses and fungi.

3. Columbus is said to have brought home “pepper more pungent than that from Caucasus,” from his travels in tropical America. In the ensuing centuries breeders cultivated their descendants—bell peppers—to be sweet, four-lobed and flat-bottomed, the better to stuff them and bake them. In the process, they may have made them more alluring to pests. As entomologist Philip Stansly of the University of Florida points out, consumers want peppers to be perfect and pretty, and farmers who fail to provide them will face huge losses – so they have greater incentive to spray.

4. Sweet corn appears at number 3 on the EWG’s “clean 15” list, but in fact the crop is doused with insecticides as often 15 times during the 35-day period from ear formation to harvest, according to Noel Troxclair, an entomologist at Texas A&M University. The insecticides are designed to eliminate corn ear worm, a pest that eats only the tip of the ear. “The average person who lives in a city has never been exposed to it,” Troxclair says. “So if they bought an ear of corn that had a worm in the end of it, about half the people would probably want to sue the supermarket that sold it to them.” The reason for sweet corn’s appearance among the clean 15? USDA tests are conducted on peeled and washed produce—and we peel off the corn husk, to which pesticide residues cling, before we eat the ear.

5. Eat more broccoli, and not just because it’s full of vitamins. Broccoli appeared on the EWG’s 2009 “clean 15 list,” and that may be in part because the vegetable is sprayed early in the season, before insects can huddle deep in the crinkles where spray can no longer reach them. But there are other good reasons for broccoli’s low pesticide residues, says Dan McGrath of Oregon State University. “I have been working with broccoli growers for about twenty five years now,” he says. “A lot has changed.” Broccoli production, he explains, “uses modern pesticides that have very short residuals. They are applied according to strict pre-harvest intervals, several weeks prior to harvest.” By the time of harvesting, “the pesticides are mostly gone (light, temperature, moisture, and microbes cause them to degrade). Modern broccoli is essentially free of pesticide residues. I know it’s hard to believe. But we have come a long ways in agriculture over the past generation.”

Strawberry image courtesy of Martino!

Apple Pie Picket image courtesy of AFL-CIO

Bell Pepper image courtesy of Joe Beasley

Sweet corn image courtesy of slappytheseal

Broccoli image courtesy of David Reber’s Hammer Photography