Nalini Nadkarni, “the Queen of the Forest Canopy,” spends her professional life clambering around in tree tops, studying the jumble of plants that grow in the high branches. I had the privilege of hearing Nadkarni, a professor at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, speak in April at the New York Academy of Sciences in a talk entitled Between Earth and Sky. I was fascinated by her eclectic range of interests, which include training prisoners at the local Cedar Creek Corrections Center to raise endangered mosses.

Yes, mosses. Most plants living in the forest canopy are epiphytes: plants that live on other plants, but derive their nutrients from the air, falling rain, and the compost that accumulates on tree branches. Most epiphytes that Nadkarni encounters are mosses, but these primitive plants, which colonized land some 450 million years ago, get little respect. “People laugh about moss,” Nadkarni told the magazine Miller-McCune. “I know that, because I give talks about moss, and I get laughed at.”

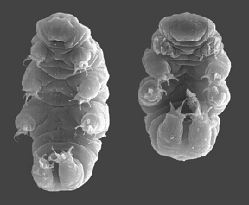

That’s too bad, because not only do mosses serve as massive water stores, but they are also home to one of my favorite animals on the planet, the moss piglet or tardigrade (also known as a water bear) a tiny segmented animal with eight legs that has been found lumbering around everywhere from the Himalayas to the equator (they have been known to survive in space.)

Nadkarni began her moss-farming prison project after she discovered trees scraped clean of their lush green fur. It turns out that mosses are in keen demand by the horticulture industry, which uses them to pack flower bulbs for shipment. Because moss grows very slowly, it can take 20 to 40 years for a stripped tree to return to its former splendor. Sad to say, she found that farmed moss can’t yet compete commercially with wild-harvested varieties.

This scientist doesn’t give up easily, though. Among her many other goals is to educate the public, in non-traditional venues, about the need to protect trees and nature. So I was delighted to discover that Nadkarni has an essay in the July/August 2010 issue of Poetry magazine, entitled “Green I Love You Green” in which she talks about the importance of using “other vocabularies,” such as poetry, to engage the public “with the importance of nature and the enterprise of science.”

I’m a keen fan of science-in-poetry, as witnessed by my column, Science Poem of the Week, which appeared on Discover Magazine‘s DiscoBlog in 2006. So I was thrilled by Nadkarni’s selection of verse, extolling both the strength and fragility of trees. Here is an excerpt of one glorious poem, “Young Apple Tree, December,” by Gail Mazur:

What you want for it you’d want

for a child: that she take hold;

that her roots find home in stony

winter soil; that she take seasons

in stride, seasons that shape and

reshape her; that like a dancer’s,

her limbs grow pliant, graceful

and surprising.

Image courtesy of Willow Gabriel and Bob Goldstein, http://tardigrades.bio.unc.edu/

One thought on “Queen of the Forest Canopy”

Comments are closed.