Exactly one century ago this year, a swashbuckling American archaeologist named Ernest Thompson was wrapping up his investigation of the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, one of the most famous of all Maya sites. Thompson had been long been fascinated by the natural 130-foot-deep sinkhole that was filled in part with water. According to one early account of the Maya, Chichen Itza’s priests cast human beings and precious objects into this cenote as sacrifices, hoping to persuade the gods to send rain, rich harvests, and relief from disease.

Exactly one century ago this year, a swashbuckling American archaeologist named Ernest Thompson was wrapping up his investigation of the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, one of the most famous of all Maya sites. Thompson had been long been fascinated by the natural 130-foot-deep sinkhole that was filled in part with water. According to one early account of the Maya, Chichen Itza’s priests cast human beings and precious objects into this cenote as sacrifices, hoping to persuade the gods to send rain, rich harvests, and relief from disease.

So between 1904 and 1910, Thompson employed both divers and dredging equipment to plumb the secrets of the cenote’s waters. He and his team recovered human bones and a host of Maya treasures–from gold finger rings to large rubber balls.

Wait a minute, you say. Rubber balls? Yes, indeed.

Three thousand years before American inventor Charles Goodyear dreamed up the process of vulcanisation in 1839 to harden natural rubber, the Maya cooked up their own technique. They added a juice squeezed from Morning Glory vines (Ipomoea alba species) to sap from the Panama Rubber Tree (Castilla elastica), then heated this brew. When they were done they had altered the polymer chemistry of the sap to create an entirely new material capable of bouncing beautifully when it was dropped to the ground. No wonder the Maya prized rubber: it must have seemed like a piece of magic.

Archaeologists have long known that the Maya used rubber to make eight-pound balls for their famous ballgame, a blood sport of sorts that sometimes ended in the sacrifice of the losers. But a soon-to-be published paper in Latin Antiquity by two researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, archaeologist Dorothy Hosler and materials scientist, Michael Tarkanian, shows how Maya inventors devised different recipes for the different kinds of rubber they used in everything from glues to the soles of their sandals.

The two MIT researchers went to great lengths to figure all this out. They spent a field season in Mexico collecting samples of rubber tree sap and morning glory juice. Back in the lab, they experimented furiously with the ingredients, cooking up one gooey batch after another and subjecting them to all kinds of tests to assess elasticity, strength and other properties.

They discovered that the Maya really knew what they were doing. By altering the proportions of the two raw materials, the ancient Mesoamericans were able to create an extremely bouncy rubber for their balls, a strong and resilient rubber for their adhesives, and a highly durable rubber for the soles of their sandals.

In recent weeks, researchers have reported several major new findings about the Maya. The ancient hydraulic engineers of Palenque devised the New World’s first pressurized plumbing systems. Caracol’s inhabitants developed a green form of urban architecture. And now it turns out the Maya were polymer chemists and walked around in footwear a lot like the rubber-tire sandals in your closet.

What next, I wonder?

Upper photo: colored drawing of Maya cylinder vase, courtesy of Madman2001

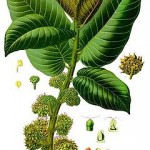

Lower photo: plate from Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler’s Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897.

Hi All,

This is a fascinating blog, which I discovered through Open Culture’s Twitter feed. I have one recommendation — please add an email subscription option. I rarely check my RSS reader and prefer to receive blog updates in my inbox. If you add this option, I’ll subscribe by email. Thanks!

Hi Chris:

Thanks for the kind words. We are working on getting an email subscription option, and hope to have it up and running very soon. Please stay tuned.

Hi Heather,

Thanks for adding the email option! I’ve just subscribed. I’ll look forward to reading future posts.

Thanks,

Chris

Our pleasure! We had that on our to-do list, but your comment hurried us along.

Another great new blog site, Heather. Your third since I first started reading your work. Don’t forget an info page, with links to your books, too.

Cool topics from your partners, too!

—–

The invention of rubber in ancient times is a fascinating topic, and you cover it well, as usual. I’ve been to Chichen Itza and will offer the following questions and observations.

Is it possible that the ancestors of the Mayans could make some kind of legal claim on the patent rights to rubber? (I’m thinking it’s not likely, but it might be worth looking into. If so, I’d think they could bolster their case by promising to use any potential royalties to help research some of the incredible archaeological heritage of the region.)

I’m also a lacrosse fan – Go Salmonbellies Go! – and although the historic North American First Nations version of the ancient game – baggataway – was played with wooden balls, the modern professional version uses rubber balls!

Do you think there’s any chance that Mayan rubber was ever traded with the peoples of the north? Or, more likely, would this incredible technological discovery have been kept for local use only?

And finally.

National Geographic wants to call that giant hole in the middle of Guatamala City a piping feature.

I’d call it a modern cenote.

What do you think?

Hi Dan:

Thanks very much for joining us here. Yes, I’ve definitely moved around a fair bit over the last year, but am planning to settle here.

Great questions. I don’t think the Maya would have a legal claim, as this invention preceded patent laws. But if Maya farmers were interested in making rubber the traditional way and manufacturing things we’d find useful today out of it, perhaps there could be a market for this. I recently heard an interview about fair-trade soccer balls, which are stitched by hand and which bring revenue into poor communities. Perhaps Maya rubber could become a fair-trade item.

There definitely seems to have been some trade in Maya rubber to the north. Archaeologists found rubber balls in the Hohokam site of Snaketown (300 B.C. to AD 1100) in the present-day Gila River Indian Community in Arizona. And the Hohokam people had ball courts and clearly loved the ball game.

I’m certainly no expert on cenotes, but it sounds to me like the big hole in Guatemala City isn’t a sinkhole. (http://news.discovery.com/earth/dont-call-the-guatemala-sinkhole-a-sinkhole.html 0. But it certainly is one big, scary looking hole.

I think the difference between a piping feature, whatever it is, and a cenote is the rock that the hole opens up in. Cenotes are in limestone, which dissolves in acidic water. This rock was apparently pumice, and a broken water pipe would just wash it away. Does that make sense?

Yes, it definitely does make sense. Thanks for adding this, Ann.