Recently I’ve started seeing examples of those much-mocked New York Times trend stories that are not about Millennials, the way the trendiest trend stories usually are. In the articles I’ve been noticing, the trend-setters are Baby Boomers — who are, according to the Times, relocating to New York City to help raise the grandkids.

Recently I’ve started seeing examples of those much-mocked New York Times trend stories that are not about Millennials, the way the trendiest trend stories usually are. In the articles I’ve been noticing, the trend-setters are Baby Boomers — who are, according to the Times, relocating to New York City to help raise the grandkids.

Now that’s a trend I could get my own 62-year-old head around.

The most recent of these pieces appeared just last weekend, a story about a young woman on the Upper East Side who was about to have a baby, and was delighted that her parents wanted to find a place to live in her neighborhood so they could help out with child care. There were a few hitches; the parents, for one thing, lived in Minneapolis, so they would have to be willing to relocate to Manhattan. (Willing they were; they were both physicians, but they were both retired.) Another hitch struck me as an even bigger obstacle: they were divorced, and they were talking about renting a one-bedroom apartment together. But good feelings for their daughter predominated, as did enthusiasm about becoming grandparents for the first time, and in the end, the Minnesotans found an apartment they liked just a mile away from their daughter and her new baby Tessa. They are taking turns living in it.

This story followed by just a few weeks another Times piece, which revealed itself as a trend story right away, with the telltale phrase “a growing number” right in the lede. (Other clues to “bogus trend stories,” according to media watcher Jack Shafer, include overuse of “weasel words” like “some,” “few,” and “seems.”) The Times piece began:

Instead of spending their golden years baking in the sun, a growing number of grandparents are choosing a grittier spot to play out their third act . . . they come for the children but stay for the city.

Cue the Monocle Meter.

Biologists have an explanation for why this trend, if it really exists, would be good for the grandkids: they call it the Grandmother Hypothesis.

The hypothesis, first put forth by anthropologist Kristen Hawkes of the University of Utah, addresses the mystery of why menopause evolved. According to Hawkes, having grandmothers around, especially maternal grandmothers, makes children more likely to survive to adulthood — an adaptive advantage to women who live past their childbearing years, who are able to pass along their longevity genes to the grandchildren’s generation.

As Natalie Angier summarized it when the hypothesis was first proposed in 1997:

When a young woman is burdened with a suckling infant and cannot fend for her family, she turns for support, not to her mate, but to a senior female relative — her mother, an aunt, an elder cousin. It is Grandma, or Grandma-proxy, who keeps the other children in baobab and berries, Grandma who keeps them alive. She is not a sentiment, she is a requirement.

One vivid demonstration of the benefits to children of having an involved grandmother comes from anthropologists at University College London, led by Ruth Mace and Rebecca Sear, who studied families in rural Gambia between 1950 and 1974. They looked at the survival rates of village toddlers — old enough to be weaned, but not yet immunologically mature nor strong enough to fend for themselves. The presence or absence of a father made no difference in how likely a toddler was to die. What mattered was whether there was a grandmother around — specifically, the mother’s mother rather than the father’s. Toddlers who had maternal grandmothers were half as likely to die as toddlers who did not.

Donna Leonetti and Dilip Nath of the University of Washington made similar findings in a study in northeast India in which they compared one culture in which young families moved in with the father’s parents (Bengali) to one in which young families moved in with the mother’s parents (Khasi). This was an experiment of nature, a handy way to see whether it mattered whether the maternal or paternal grandmother was doing the nurturing. And it did. Among the Khasi, where it was the mother’s mothers who were the resident grandmas, children had a 96% chance of surviving the first five years of life. Among the Bengali, where the active grandmas were the father’s mothers, children had just an 83% chance of surviving to the age of five.

American families are not Khasi or Gambian, of course, but there might be something to the grandmother effect even here. After all, Michelle Obama probably couldn’t have been as good a mother as she’s been during her tenure as First Lady if her own mother, Marian Robinson, hadn’t decided to relocate to the White House in 2009 so she could, as she put it, “get to be Grandma” and help her granddaughters “grow up before my eyes.” Nor could many other young mothers, whose mothers or mothers-in-law are willing to put in the time to do some serious babysitting, manage to do as good a job as they do juggling the needs of their children while focusing, at least some of the time, on their careers.

It used to be easier for grandmas to provide this kind of help. A generation ago, when the average age at first birth for a new mother was 25, it was typical for people to become grandparents in their early 50s, when they were still relatively young, relatively energetic, and relatively able to take over when new parents were at the end of their rope. That meant that when the grandchildren were teenagers, the grandparents were in their late 60s, possibly newly retired, still energetic, and able to act as a bridge between rebellious teens and their sometimes-mystified mothers and fathers.

Grandma and Grandpa continued to have a role in the grandchildren’s lives as the children grew up: the kids graduated from high school, and the grandparents were in their early 70s; graduated from college, and the grandparents were in their mid-70s; married, and the grandparents were in their early 80s and probably still sufficiently agile to get to the wedding. Some lucky grandparents were even able to stay alive long enough to watch their grandchildren have babies of their own.

Quick out of the gate during my own growing-up years, I’d done my part to keep things moving along according to this brisk schedule. I had our first daughter at age 26, our second at age 30. But as I moved through my late fifties and into my sixties, I saw the timetable stalling, and worried that I’d never be a grandma early enough for the rest of that lovely scenario to spin out. For the first time in my life, it seemed, my own ability to have my ducks in a row depended on someone else’s timetable.

I’d always pictured my final years being peppered with big-extended-family scenes, with my Thanksgiving table — or, depending on my angst level that day, my deathbed — amply populated by grandchildren well-settled in their own lives, maybe bringing along a couple of babies of their own.

Would my daughters get a move on, I wondered, in time for all that actually to happen? I had done my part on schedule; what was taking them so long? My crabbiness extended to their entire cohort: why are young women today so sure they have all the time in the world to make decisions about childbearing? And don’t they realize that if they deny their kids active, involved grandparents, they’re denying them something important?

That’s why I’ve always liked the Grandmother Hypothesis; it gave a scientific explanation for something that did indeed feel biological, a primal urge to have a baby in my life again, to hold a bundle of perfect, pure potential, stunning in its unknowability — this time holding that bundle consciously, attentively, without all the stresses associated with early motherhood and fears about somehow ruining my precious child. I wanted to be a grandmother who was young enough to take part in the baby’s life, to take him or her on outings, to do day care pickup, to travel to Europe together, be around for soccer games, for school plays, for college graduations, for weddings.

My crabbiness dissipated in June when our younger daughter had a baby, a delicious little girl with chubby cheeks and the world’s sweetest disposition. I don’t have to move halfway across the country to help out, either; my husband and I already live in the same city as our daughter and her family, just a (long) subway ride away. We’re not trendy enough to be offering ourselves up as routine day care — we’re both very emphatically not retired — but we’re happy to be asked over to see the baby every week or so, and we offer to watch her every chance we can, ostensibly so her parents can go out on their own. I can’t wait for the day when our granddaughter recognizes us as Gran and Grumps; we probably strike her now as just part of a long line of very nice folks who adore her. Till then, we’re delighted to be able to visit often and breathe her in, reveling in the amazing, ever-shifting beauty of a four-month-old child. And if our presence somehow offers her a better shot at a long and healthy life, how cool is that?

__________

Robin Marantz Henig is a freelance journalist in New York and the author of 9 books on science and medicine. On Twitter as @robinhenig, she wastes a lot of time and calls it research.

__________

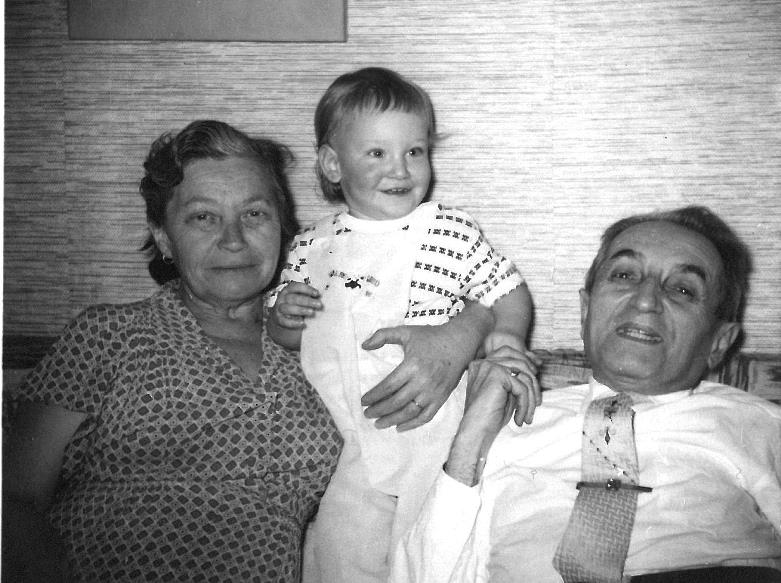

Photo: The author at about the age of 1, flanked by her maternal grandparents, Yetta and Joseph Stern. Photo by Sidney Marantz.

You should look up the DWIL forum for a very different perspective on this.