Seeing a mammoth is not the same as looking over a zoo wall at a modern elephant, or even standing next to a live, gray, wrinkled wall of flesh with scant, coarse hairs. Watching the flexible, prehensile reach of an elephant’s trunk and the slow cross-wise chewing of hay, I’ve found it hard to see the larger mammoth inside.

Seeing a mammoth is not the same as looking over a zoo wall at a modern elephant, or even standing next to a live, gray, wrinkled wall of flesh with scant, coarse hairs. Watching the flexible, prehensile reach of an elephant’s trunk and the slow cross-wise chewing of hay, I’ve found it hard to see the larger mammoth inside.

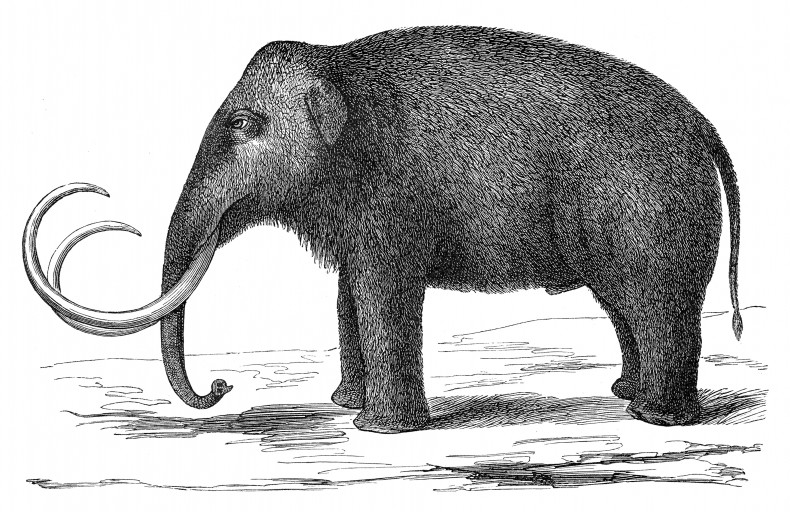

Elephants and mammoths are obviously related, both proboscideans evolved from a trunked African animal the size of a pig some 60 million years ago, eventually becoming the largest land animal on earth. The earliest version of the mammoth, Mammuthus subplanifrons, originated in the African tropics about 5 million years ago. A later mammoth, Mammuthus meridionalis, entered forests and grasslands in Europe and Asia about 3 million years ago, eventually leading to the famed wooly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius, which adapted to cooler, more arid treeless conditions in the north from the British Isles to eastern Siberia and into North America. The wooly mammoth was a latecomer to the New World, arriving from Siberia across the land bridge only 100,000 years ago. A previous mammoth species had arrived in North America a million years earlier and moved into warmer more southerly parts of the continent where it evolved into the what is known as the Columbian mammoth, Mammuthus columbi. This was one of the larger proboscideans to have ever lived, up to 13 feet tall at the shoulder.

In museum collections, I’ve looked for this animal by running my hands along the arcs of their tusks, 10 or 12 feet of solid ivory, colored chestnut from time in the ground. In the clean lighting and gentle hum of air ducts, I still couldn’t see the actual beast. Taken out of the context of its environment, I saw paleontologists and plaster jackets more than I saw mammoths.

The best view I ever had of this animal was in the gypsum wastelands of a bombing range in southern New Mexico where mammoth tracks have been repeatedly discovered. These tracks belong to the larger species, the Columbian mammoth, and they have been reported from a number of locations across the active White Sands Missile Range. These are not hardened fossils but stand out in sediment that is still soft and eroding. About 20,000 years ago, a shallow, crystal-blue lake rested in the bottom of Tularosa Basin. The Rio Grande was not flowing toward the sea at the time, but emptied into this closed basin. Along muddy shores walked all manner of Pleistocene life, dire wolves, saber-tooth cats and camels. The most impressive, leaving clearly defined trackways, were mammoths.

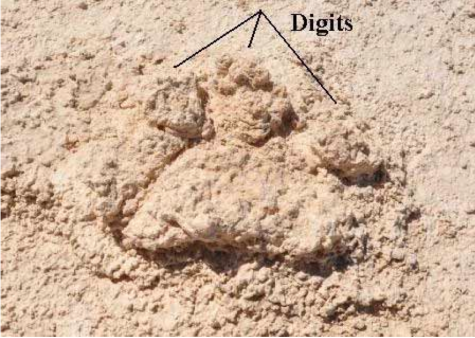

I traveled on the bombing range with a small group, including a former military ordinance expert who had defused bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan, a man who kept mentioning the kinds explosives we might find out here, and the various ways they could accidentally kill us. His tales of warfare seemed far away as we traveled across this lifeless, wind-stripped expanse, our steps passing through thousands of years. On a soft, pinkish-gray horizon of gypsiferous clay, we came upon our first set of tracks. They weren’t raised cleanly like the “pancakes” paleontologists and geologists had been photographing and publishing from other parts of the range. Instead, they looked like large, badly-cooked omelets slapped on the ground, each one a roughly circular impression of a mammoth’s step. The weight of the animal had pressed into mud making it denser, slightly more resistant than surrounding sediment so that it left a concave impression. Several of these stretched before us, laying out the gait of a large, moving animal.

Here, I finally saw my first mammoth, a switch in my imagination flipped. The body rose up from the ground in front of me, resolving in mid-air. Even when I was a kid standing under towering skeletons in museums, I had not seen a mammoth so distinctly, the tracks giving birth to four long legs the size of chimneys, the long-bones vertically oriented to post up the weight of what must have been an 8-ton animal. The slope of its back rose to the shoulder hump, the muscular curve of the neck, and the hairy crown of its head. The head was not raised, but lowered slightly, attentive to the ground, massive tusks descending from its face and nearly touching the wet substrate. Of southern, warmer ilk, this mammoth was not shaggy like its wooly northern cousin. I could see down to its skin under a sheen of hair. Its muscles lumbered from one side to the next, slow steps initialized by rear legs, followed by the corresponding fore, tusks gliding ahead like the cutting edge of a bulldozer.

Careful not to step too close to the tracks, for they were fragile, I walked to the mammoth’s side, measuring its steps with my own. The animal seemed unalarmed, perhaps unable to see me as it plodded across a wet, shallow shoreline. After about thirty feet, the tracks sanded back into oblivion, worn away by weather. The mammoth thinned into nothing along with them. It drifted away until nothing remained but a space in the air.

More than 700 individual tracks of various mammals have been documented around the range, and one mammoth trackway consists of 57 prints from a single animal. Most are mammoths, with what appears to be camels sprinkled in, and 24 individual cat prints, the gait and size suggesting the saber-tooth cat Smilodon fatalis or the American lion Panthera atrox. One predator track in particular looks to be a short-faced bear, the back edges of two digits pressed more deeply into the sediment than the rest of the foot, indicating that the animal was digging its toes into the soft, muddy surface as it walked.

With textures as friable and as temporary as pastries, these will last decades at most. Though they have been in the sediment for at least 20,000 years, weather has exposed them for only a short time, and is in the process of wearing them away. Canid tracks documented in 2010 were practically obliterated by heavy rains before researchers returned to barely find them again in 2011. Other, older tracks wait in the ground below, and in the same manner will be revealed and discarded over time. What we witnessed on this day was a moment, a ghost, a memory about to be lost.

Once we identified the first tracks, more appeared. Mammoths had been traveling one direction and another, hard to tell if they were in each others company days, weeks or years apart, none coming close enough to overlap and give a sense of superposition. Between them was the rough scribble of what looked like smaller animals trotting along the shore leaving their lighter, staccato prints. By smaller, I mean possibly dire wolves or saber-tooth cats. From these sediments, paleontologists have found actual remains, including the Ice Age bones of horses, camels and parts of mammoth teeth, as well as signs of many smaller creatures: ducks, voles, frogs and rabbits. What is now a treeless wasteland was once a rich country far south of the ice sheet. Researchers have found impressions of what appear to have been tree-falls along the lake, possibly the acts of mammoths doing the same as modern elephants, pushing over trees in a place now absent of most living things.

Trail networks from mammoths would have crisscrossed a landscape that was then a juniper woodland coming down to the edge of the lake. As we walked among trackways, careful not to step directly through them, mammoths appeared from the ground all around us, the Ice Age falling back into place.

When we found pieces of shrapnel, they were almost startling, as if they’d fallen out of a time machine. How could there be metal here in the Ice Age? The bomb expert would go up and kick them or pick them up, looking for a sign of how they’d exploded, or any markings that might say what they had been. He was seeing the shapes of missiles, the flashes of impacts. At that moment, time seemed to open wide. We were not in one moment or another. He’d hand me a small piece of twisted metal, or the green-tinted point of a 50mm projectile, as if showing proof of how much time has elapsed since mammoths walked this glimmering lake shore, how many ages have come and gone.

Images: Shutterstock and White Sands National Monument

The Waco fossil beds have Columbian mammoths; Craig needs to come to Texas!