I have an assignment from a magazine to write a profile of a woman astronomer. I am delighted about this: the magazine is excellent, the editors are superb, and the woman astronomer is impressive. I did notice that the assignment came just before the magazine announced publicly it needs to redress its problem with a gender balance that favors males, and that both I and my profilee are suspiciously female. But I honestly don’t care.

I have an assignment from a magazine to write a profile of a woman astronomer. I am delighted about this: the magazine is excellent, the editors are superb, and the woman astronomer is impressive. I did notice that the assignment came just before the magazine announced publicly it needs to redress its problem with a gender balance that favors males, and that both I and my profilee are suspiciously female. But I honestly don’t care.

What I won’t do, however, is write about this astronomer as a woman.*

Not that I haven’t done that before: a while back, editors were commissioning one story after another about women in physics, women in astronomy, and I ran all over the place interviewing women physicists and astronomers about their careers in overwhelmingly (90 percent is a good rough number) male fields: what did they face, how did they deal with it.

Not that I haven’t done that before: a while back, editors were commissioning one story after another about women in physics, women in astronomy, and I ran all over the place interviewing women physicists and astronomers about their careers in overwhelmingly (90 percent is a good rough number) male fields: what did they face, how did they deal with it.

I learned that sexual harrassment is frightening when the guy wanting your sexual attention is your advisor. I learned that feeling like the only leopard in the room is hard when the room is full of tigers. I learned that the obvious response to hearing that boys are better at math is to be better at math than boys are. I learned that seeing another woman doing what you want someday to do is heartening. I learned that marrying another scientist and then finding two rewarding jobs in the same city (“the two-body problem”) almost guarantees that the job one of you takes will be less than rewarding. And living on the other side of the continent from your spouse can be tenable for years. And being what one astronomer called a two-person, one-parent family is also tenable but wearing. I learned that in the arrogant and competitive culture of the physical sciences, you’d best learn what another astronomer called “jostling and hurling.” I learned that the motivation for being an astronomer regardless of the battles is that the stars and galaxies are so beautiful and their behavior so intricate and right.

I learned all that maybe 10 years ago. At the time, the fraction of tenured astronomers who were women was 7 percent. Now it’s 15 percent. Every institution hiring astronomers has policies, oversights, committees, whatever is necessary to assure gender equity. The American Astronomical Society has a Committee on the Status of Women in Astronomy that’s active and current. But 15 percent is still pathetic. And a rigorous study by a prestigious outfit showed that underneath the ancient and stupid list of inequities – lower salaries, longer times before promotion, larger numbers in lower ranks, tiny numbers at the highest rank – is a completely unconscious judgment by men and women both that women just aren’t as good.

Ok fine I give up. The problem has been noticed, is being attended to, and isn’t going away any time soon because it’s deeply cultural. I mean, an essay titled “Why Bias Holds Women Back” by the chairman of astronomy at Yale (oh my, a woman!) is interrupted by a link about skinny models with a picture of a skinny model in a deck chair upside down and in a bikini. I don’t see any solution other than time and perseverance. Meanwhile I’m sick of writing about it; I’m bored silly with it. So I’m going to cut to the chase, close my eyes, and pretend the problem is solved; we’ve made a great cultural leap forward and the whole issue is over with.

And I’m going to write the profile of an impressive astronomer and not once mention that she’s a woman. I’m not going to mention her husband’s job or her child care arrangements or how she nurtures her students or how she was taken aback by the competitiveness in her field. I’m not going to interview her women students and elicit raves about her as a role model. I’m going to be blindly, aggressively, egregiously ignorant of her gender.

I’m going to pretend she’s just an astronomer.

___________

*Unless the editors badly want me to, then I will. But I won’t like it.

___________

UPDATE: Christie Aschwanden turned my second-to-last paragraph into the Finkbeiner Test, took it, and ran.

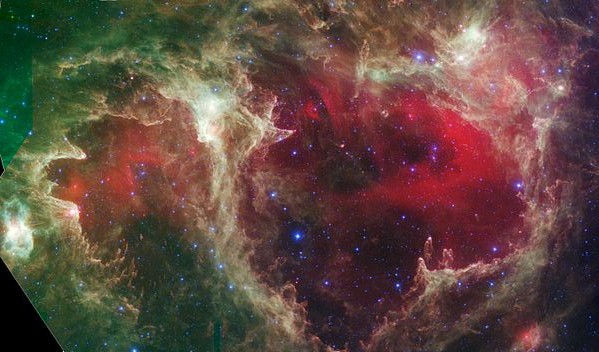

Both photos from Wikimedia Commons of two different places where stars are forming, both seen in the infrared.

*cheers*

I hope the editors let you do it!

Thank you, Liz. I suspect they might. However, I just found myself writing the sentence, “. . . and she’s the only woman to win the prize ever.” Now what shall I do? Go back on my vows?

Good for you! Hooray!

Good for you, Ann. Besides, if one point of the story (in the editor’s mind, anyway) is to highlight the fact that you don’t necessarily have to be a man to be a very successful astronomer, simply writing about a woman in the field will achieve that without your ever having to say it explicitly. That’s pretty much how I approach it too.

Thank heavens.

I am curious if readers will assume the subject is male.

Hooray! What a good plan.

I wrote a profile of a queer macArthur-winning astrophysicist + a person who won 2 top awards in the field of astronomy last year but is working as an engineer now..

They both made it to the Best of .. Science Careers last year.

Could I have avoided saying that they were women. Maybe/maybe not. Should go back and read my pieces.. Good luck with yours.

http://sciencecareers.sciencemag.org/career_magazine/previous_issues/articles/2012_06_01/caredit.a1200061

http://sciencecareers.sciencemag.org/career_magazine/previous_issues/articles/2012_10_19/caredit.a1200116

It’s about time. Thank you, Ann!

I did an article for a similar sort of magazine recently, which by coincidence also had a male problem. (Is this so common?) At the beginning of the assignment I was given a list of 10 men I should consider interviewing. And this in a field absolutely riddled with women.

And no you should not go back on your vow. Don’t mention the “first woman” prize. When I read about first women these days, it’s not a good feeling. It makes me feel the way I did when I glanced into the doorway of the Princeton club’s then empty dining room in about 1987. It was dark and unremarkable. But a brass plaque set in the carpeted floor read: “Where women cease from troubling and the wicked are at rest.” Being the “first woman” is about how things used to be.

Ooooh, Jenny, I like that. You’re exactly right and I’m taking that sentence back out. NOW.

Bravo, Ann! I think you are 100% right!

Wonderful piece Ann; I think you’ve captured the angst and frustration many in this field feel about the agonizingly slow gains women (and minorities) have made in Astronomy. But I also have optimism, as there is action in the community, women in authority and many who are making conscientious choices to recognize and change the environment – and have the power to do so.

My other foot is in Physics, however, and the situation is agonizing. Demographics have stagnated for the past decade; in our department we have undergraduates who have never been taught by a female Physics (or Math or Chemistry) professor in 4-5 years. Our women are constantly reminded in subtle (and not so subtle) ways that their choice of major is “remarkable” and “unusual”. This is coupled with a department that thinks no action is the most equitable path. I am constantly impressed by our women’s fortitude in such conditions.

I had to think about your arguments carefully, as I recognize the importance of role models for women in the physical sciences, particularly those who did great things without having to sacrifice a “normal” life (or at least what passes for normal when you’re a scientist). Nevertheless, I applaud your decision to not make this article “about a women _________”, and just “about a _______”. I agree that we have to stop attaching genders as adjectives and qualifiers if we are to move science forward as equals.

Ann, I really enjoyed your essay.

There are famous astronomers who are women – Sandy Faber, Martha Geller, Anneila Sargent, Neta Bahcall, Andrea Ghez, Marsha Rieke, Debra Fischer, Sara Seeger, Wendy Freedman, and others. They are the minority.

Perhaps someday we will reach parity between men and women. That is a first big step, and one which has a clear metric. It is a goal we must reach and we are two decades away from this.

But when we reach it, where are we? Is is a good thing that we are gender neutral?

I am reminded of the prize talk by Chryssa Kouveliotou at the AAS, one of the great astronomers we have today in the US (and one of my heroes in our science). At the very end of her talk, she took time to remember her colleagues – and her husband – who have passed away. There was deep emotion in her voice remembering them, and how they had been part of her life. She also is famous for helping, nurturing, and collaborating with many astronomers, more so that probably any other astronomer today (there is actually a metric for this, and she was the highest ranked astronomer).

I hope as we drive our community toward equality in gender, we don’t lose the feminine qualities in our science, honoring the people we have loved, and helping those less fortunate or vulnerable to succeed. We need to reward and advance these scientists too, not just fast-talking cosmologists like me. If we end up rewarding traits that have made many male astronomers famous, then we will not have succeeded.

So I wish you well in your article. I hope someday we will not have to point out the problems of gender, but celebrate what gender brings to our science.

**The editors don’t badly want you to.

I think it’s unlikely that readers will assume the astronomer in question is male unless 1) she has a gender-neutral first name (possible) and 2) Ann never uses the word “she” (pretty darned unlikely)

Helen: Oh gloriously yay! I mean that.

Nick and Adam: You two give me faith. Definitely role models work — my astronomer dedicated her PhD thesis to her role models. I’m talking only about how I as a writer handle this. And I think I love the idea of the feminine qualities of science, though I might just be under the protracted influence of Ursula LeGuin. But with the kind of intelligence and sensibility you guys have, really, it’s going to be ok, isn’t it. Isn’t it?

so what happened? where is the profile? i am dying to see it.

It’s been surrendered to the editors’ tender mercies. The timeline is out of my hands and from now on, I just do what I’m told. Short answer: I don’t know.