Spend enough time on the internet and you’ll spot one. They tend to sprout in the comments beneath articles like little text cabbages:

Spend enough time on the internet and you’ll spot one. They tend to sprout in the comments beneath articles like little text cabbages:

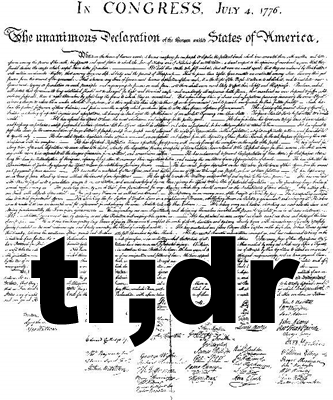

tl;dr

tl;dr

tl;dr

Unpack them and you’ll find an accusation: “too long; didn’t read.”

This isn’t some hot new trend I’m cluing you into: tl;dr hasn’t been de rigeur since it became Urban Dictionary’s word of the day in 2005. Unlike most slang of the moment, however, over the past seven years, it has proliferated. Its enduring popularity and ubiquity is a testament to the fact that this concise little construction calls out what might be the fundamental problem of the internet age. As such, tl;dr is the battle cry of the internet generation. And the concise way it encapsulates the problem might also be a hint to its ultimate solution.

If you’re like most people, your first reaction to the term tl;dr was a giant eyeroll. Even on Urban Dictionary — where the internet’s elite meet to smelt the lingo of the future — the term has proved controversial. “A sign that, not only is someone too lazy and stupid to read but, clearly, too lazy and stupid to even type out four words indicating such,” sneered an anonymous contributor.

I was once like you, bitter Urban Dictionary guy. After all, what could be a more perfect distillation of the dumbing-down effect of the internet? Google is robbing us of the ability to concentrate. The internet and Facebook are making us stupid. Against this backdrop, tl;dr becomes a tempting metaphor for the brain rot of a tech-addled generation.

But what if it’s not? What if, instead, tl;dr is an elegantly concise summary of the internet’s information problem?

As you will have heard, the internet is just too damn big. At last count, it was comprised of more than 7 billion web pages, and there’s no quality control. The received wisdom is that this is a curation problem. In his book Too Big to Know, David Weinberger explains that in the days before the internet provided unlimited space, the very fact of publication was enough to let you know that something was worth your time. Some publisher had pre-screened it; some editor had slaved over it; some magazine had devoted ad revenue to paying someone to write it.

The internet changed the rules. Now there are fantastic gems no one gets paid to write. Conversely, just because someone got paid to write something is no longer a guarantee that you should spend your time reading it.

And so, good curators have found their niche. Maria Popova makes a living plucking the finest flowers from the internet’s walled gardens. Maybe your curator is the New York Times, maybe it’s Andrew Sullivan. But most of us now rely on these filters.

The problem is that this makes our world smaller. After all, no filter catches everything. I don’t want my boundaries to be restricted, even by people I trust to tell me what’s important. What if I want to break free of my filter bubble?

Then I’m taking my chances. Attention means time, and if we have a limitless space into which we can dump limitless information, the most precious resource becomes time to sort the wheat from the chaff. When I’m staring down the abyss of the open internet, how can I know what’s worth my attention?

And that’s how tl;dr reveals the growing fundamental mismatch between a medium and the ability to communicate effectively within that medium.

When languages have failed us in the past, we’ve adapted them in surprising ways. After the people of La Gomera in the Canary Islands realised they couldn’t shout long distances because the terrain attenuated their voices, they switched to a whistling language that lets them communicate without shouting.

The whistling language is optimised to solve the problem of long-distance communication. Other languages are optimised for information density. As a study from the Université de Lyon showed last year, for example, some spoken languages carry more information per unit.

Mandarin and Vietnamese contain more information per unit language, owing partly to their tonal inflections. Tonal languages like Mandarin encode information not only in the syllable but in the tone; the same word carries a different meaning if it’s uttered like a question or like a statement. That makes it harder for non native speakers to learn, but for people who are fluent, it packs more complex meaning into smaller carriers.

Can we apply any of these lessons to written language? Is there a way to increase the information density of our text? You probably saw this coming, but we’re already doing it.

Call it what you will — leetspeak, Internet-speak, or your favourite epithet here — it is evolving the written language to encode significantly more information. We all know that guy who insists on replacing “you’re” with “ur”, a linguistic travesty that first emerged to save time typing complex messages on clunky cell phone key pads.

As the language gets ever more compact, it also relies more heavily on a shared set of familiar acronyms: lol, brb, idk, tl;dr. But to understand these acronyms, you’re also relying on in-group knowledge and context, and if all conversation participants aren’t on the same page, the confusing acronyms can lead to some serious contextual whiplash. My personal favourite is FTM, which on fertility boards identifies you as a Full Time Mother, but anywhere else lets people know you’re a Female To Male transsexual.

Tonal languages smuggle extra information in fewer syllables by varying the tone. There are ways to translate that to written English as well, and you’re already familiar with them:  the emoticons that spazz up the joint, signposting your emotional spectrum from happiness all the way to inarticulable emotion-salad. They add information tonality to a sentence, allowing you, for example, to deduce whether something was written sarcastically. One 2-centimetre emoticon can spare you an entire paragraph of explaining the complex emotional lens through which the reader should interpret the tenor of your argument.

the emoticons that spazz up the joint, signposting your emotional spectrum from happiness all the way to inarticulable emotion-salad. They add information tonality to a sentence, allowing you, for example, to deduce whether something was written sarcastically. One 2-centimetre emoticon can spare you an entire paragraph of explaining the complex emotional lens through which the reader should interpret the tenor of your argument.

Not everyone is excited about the new information delivery system. It’s been well documented that the youngins can’t spell a complete sentence because of the way they’ve grown up with a medium that rewards brevity and wit over Strunk & White. “Capital letters? What are those?” complained my friend Laurel, a history professor at a US college. Internet-speak has been spotted everywhere, infesting everything from college papers to GSCE exams.

In 40 years, will the word “you’re” read as absurdly formal as “forsooth” does today? Will the editors of tomorrow be stayin l8 2nite kthxbai? I would say the question is not whether the language will change but how soon. But this is not a cause for alarm. Just as the whistling language is restricted to public communication, internet speak will only go where it’s needed.

But even a superdense information delivery system has its limits. After all, 7 billion pages are the definition of tl;dr. The real solution, as we all know, is a Thunderbolt plug straight to the back of the neck. Then we can all know kung fu.

Image credits:

weird emoticons:

I see tl;dr, I get mixed feelings, one of which is “Thank God somebody came out and said it.”

According to the links, English is already an information-dense language. Should we densen it further? What do you say to that, young Sally?

Fantastic gem, indeed! Thanks for my first belly laugh of the day.

Well written piece. Enjoyed it thoroughly. I am still reluctant to switch to shortened phrases, but this makes a strong case of “use where appropriate”.

Thanks, Shree. I actually can’t believe I wrote this piece. I still shudder when I get a text asking me how “ure” doing.

And Ed, the n-dash and the semicolon are my favourite bits of punctuation. I only wish I could use them exclusively.

Let us not forget that tl;dr is encouraging otherwise very stupid people to use the semi-colon.

Em > en

I used to prefer em to en as well, but the British way of doing things got in my head. Now em-dashes look obnoxiously long and imperious. En dashes accomplish the same purpose but in a reserved way. Oh my God, what is happening to me??

Anyway I would also like to take this opportunity to express my disappointment that no one picked the low hanging fruit to give this (long) post a tl;dr.

Sigh.

This is lovely! I am surprised, however, to see brevity set in opposition to Strunk & White. In some cases, surely tl;dr is the refuge of a lazy reader. But in others, might it not be the modern distillation of that famous style injunction, “Omit needless words”?

I love long-form writing (hey, I read LWON) but less skilled writers constantly use too many words to say too little, on the interent as elsewhere. tl;dr could be a noble tool of the critical reader and the English teacher alike.