It’s not the setup of a bad joke. For years, the U.S. military has likely used brain scanners to try to read the minds of suspected terrorists. Some bioethicists have argued, and I tend to agree, that using neuroimaging during interrogations is not only ineffective, but could also exacerbate the abusive treatment of prisoners of war.

It’s not the setup of a bad joke. For years, the U.S. military has likely used brain scanners to try to read the minds of suspected terrorists. Some bioethicists have argued, and I tend to agree, that using neuroimaging during interrogations is not only ineffective, but could also exacerbate the abusive treatment of prisoners of war.

We want terrorist suspects to disclose reliable information. So the push for technology that can distinguish truth from deception makes sense, especially when you consider how older methods have failed. Physical torture, of the sleep deprivation, stress positions and waterboarding varieties, almost always, if not always, gives interrogators buckets of unreliable information. (It has some pesky ethical problems, too, but I’m not going there.) ‘Truth serums,’ such as scopolamine, sodium pentothal, and sodium amytal, act like sledge hammers on rational cognition and produce punch-drunk gibberish no more illuminating than the pronouncements of David After Dentist. And then there’s the polygraph, whose infamous squiggles reveal not the truthfulness of information, but rather the interrogee’s emotional response to it. Polygraphy is pretty much useless in all situations, not to mention those in which the subject is exhausted and/or drugged and/or relying on a translator.

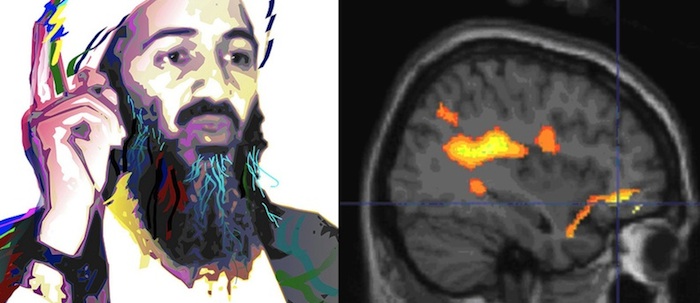

Enter our colorful hero, the brain scan. The most famous is called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures blood flow in the brain.

“Light years in effectiveness beyond a polygraph, an fMRI scan can distinguish — instantly, in real time — when someone is lying as opposed to telling the truth, as different regions in the brain would light up,” blared a 2003 article in the Washington Times with the headline: Interrogating KSM: How to make the al Qaeda terrorist sing in an hour. Before you blame the hype on journalists or the lay press, consider what neuroscientist Daniel Langleben told Nature in 2005: “We can’t say whether this person will one day use a bomb…But we can use fMRI to find concealed information. We can ask: is X involved in terrorist organization Y?”

This was the message of fMRI lie detection advocates years ago, when they debuted their work. The findings seemed to seduce everybody. And they spurred the launch of dozens of start-ups that sell brain scans to help alleged criminals defend themselves and companies conduct market research. The trouble, then and now, is that the brain-scan lie detector is no more reliable than the polygraph.

There are dozens of reasons why, but I’ll give you the top two. The research that supports those claims comes from experiments in which volunteers lie in a scanner telling various truths and lies. Neuroscientists analyze brain scans by essentially averaging the activity of all of the participants’ brains during lying versus the activity of all of their brains during truth-telling. Studies have found, for instance, that when we lie, we tend to have more brain activity in a certain spot in the prefrontal cortex. That’s fascinating, for sure, but the problem is that it’s a group average. That means that some individuals show more excess frontal activity than others, and the predictive value of any one scan is relatively low, with accuracy rates around 70 to 80 percent (remember that the accuracy rate of a blind guess is 50 percent).

The second, more difficult issue is that scientists create laughably artificial scenarios with extremely clear-cut truths and lies, such as whether a playing card that pops up on the screen is the same one the volunteer had received earlier inside of an envelope. The volunteers usually have a small financial incentive for following instructions, too. In contrast, can you imagine how this would work during a high-stress interrogation? The suspect might subvert the technology simply by thinking of something that was true, or of something entirely unrelated. What’s more, the same regions of the brain that light up during lying are the ones that we use for all kinds of high-level cognition and emotion — such as, say, intense anxiety over whether your captors are going to hurt you.

Yet just as scientific evidence hasn’t stopped the military from using unreliable old technologies, apparently it hasn’t stopped them from using unreliable new ones. Beginning in 2002, psychologist Jean Maria Arrigo has corresponded extensively with a retired U.S. Air Force intelligence officer to glean information about interrogations. Here’s what he or she reportedly told Arrigo* about brain scanning technologies:

Brain scan by MRI/CAT scan with contrast along with EEG tests by doctors now used to screen terrorists like I suggested a long time back. Massive brain electrical activity if key words are spoken during scans…Process developed by neuropsychologists at London’s University College and Mossad. Great results. That way we only apply intensive interrogation techniques to the ones that show reactions to key words given both in English and their own language.

This is just one person’s perspective. But given how brain scanning has taken off in the private sector, it’s not hard for me to believe that the military has also been using it for years**. Scientifically, for reasons I described, that’s a waste of time and resources. But some ethicists say that it’s worse. They point to studies showing that non-scientists tend to treat brain scans as more credible and authoritative than other types of information. You can see it plain as day in the intelligence officer’s quote: we only apply intensive interrogation techniques to the ones that show reactions.

Or more bluntly: they’re relying on unreliable blips of brain activity to determine which detainees will be tortured. I sincerely hope this is a cynical and flawed interpretation. But if not, if not…

What do you get when you put a terrorist inside of a brain scanner? We don’t know. The question has enormous implications for science, in peace and in war, and so deserves an answer, or at very least, a public discussion.

—

*The so-called Arrigo Papers are on file at the Project on Ethics in Art and Testimony in Irvine, California, and at the Intelligence Ethics Collection at the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University.

**On the ‘Research Projects‘ page of the website of the National Center for Credibility Assessment, at least one study involves a p300 brain-wave test, which is a lie-detection method that relies on electroencephalography (EEG), in which electrodes are placed over the scalp to measure brain waves. Under ‘Focus Areas,’ the page lists, in addition to behavioral measures, eye-tracking, and polygraphy, ‘central nervous system measures.’ Curious.

Images from Djoko Ismujono, NIMH and Wikimedia Commons

“The trouble, then and now, is that the brain-scan lie detector is no more reliable than the polygraph.”

True. But while the polygraph seems to have stalled out some decades ago, it is at least an open question whether imaging techniques can be improved as basic research continues.

Shameless self-promotion: I recently published a paper related to this – although, as I knew would happen, it is already out of date in some ways.

http://neurodojo.blogspot.com/2011/05/how-my-ethics-of-brain-scanning-paper.html

maybe a combination is required. Give “truth serums” or maybe a general anesthetic at a low enough dose to make the subject drowsy but not unconscious, then whisper a word in the subject’s ear then see which parts of the brain light up